Amid ongoing climate devastation and an over-touristed Hawaii, Mariah Rigg’s debut story collection, Extinction Capital of the World, paints a native’s viewpoint of the islands, their complicated colonial history, and what is at stake for the endangered ecosystem. Each of the ten stories in the collection is deeply rooted in the Hawaiian islands, both as setting and as a central tension for many of the protagonists grappling with the hold their place of origin has on them and what their future with the islands may look like.

While the stories are set in the present day, Riggs eschews linearity in her storytelling in favor of a circular structure that loops seamlessly back and forth between past, present, and future. They often take an expansive, at times omnisciently wise, point of view that underscores the interconnectedness of people and their actions.

For instance, the collection’s opening story, “Target Island,” centered on the life of a man named Harrison, begins “[f]ifty-eight years before Harrison’s granddaughter is born,” and then “[f]ifty-one years before,” and “[f]orty-one years,” stretching all the way up to “[t]hree days after his granddaughter, Lila, is born.” Across these years, the narrator traces the timeframe from the dropping of a bomb by the U.S. government on the island of Kaho‘olawe to the decades-long and still-ongoing fallout from that bomb. The effects are seen both on the environment, with cleanup still unfinished, and the people, as Harrison has developed cancer, just like his father did. And even with this expansive timeline, Harrison is able to see even further into the future and reach back further into the past — imagining Lila taking her children to this island one day and what this land’s cliffs looked like “before they were razed for resorts and Army Reserve homes” — offering a portrait of the island as a living, evolving organism, rather than a static snapshot ripped out of history.

Further underscoring the theme of interconnectivity is the fact that the stories are linked, though subtly. Mindful consumption and an alert eye are necessary to spot the ties, which are often as understated as a repeated name or a minor detail. But putting in the close-reading effort pays off, adding an additional layer of complexity and depth to the stories that already shine individually. As just one example, the collection’s sixth story, “Field Dressing,” picks up with Harrison’s son as he reevaluates an old friendship after his father’s death from cancer. It’s a detail that resonates more than it might have had we not gotten an intimate portrait of that man pages earlier. This collection makes the case that with greater context, comes greater depth. Riggs, unsurprisingly, sums up this sentiment perfectly in an interview with Writer’s Digest, speaking of unintentionally arriving at a story collection that was linked: “I realized that what I’d thought had been separate lives was really a universe.”

This circling approach to storytelling, which enfolds a future not yet written and a past never entirely known, also instills an openendedness that can feel challenging to feel entirely satisfied by. Though then again, that is not an entirely inaccurate reflection of life, where we are stuck existing in a present that is suspended between what came before and what will come next, with no clearly decreed endings or neatly wrapped-up conclusions. Certainly, that inconclusiveness and ungraspability are not unfamiliar to many of the situations evoked in the collection, such as fleeting yet intense young love connections or strained relationships with parents or spouses.

It is, however, a reminder to zoom out and zero in our attention, lest we overlook what lies right before our eyes, and our place within it.

FICTION

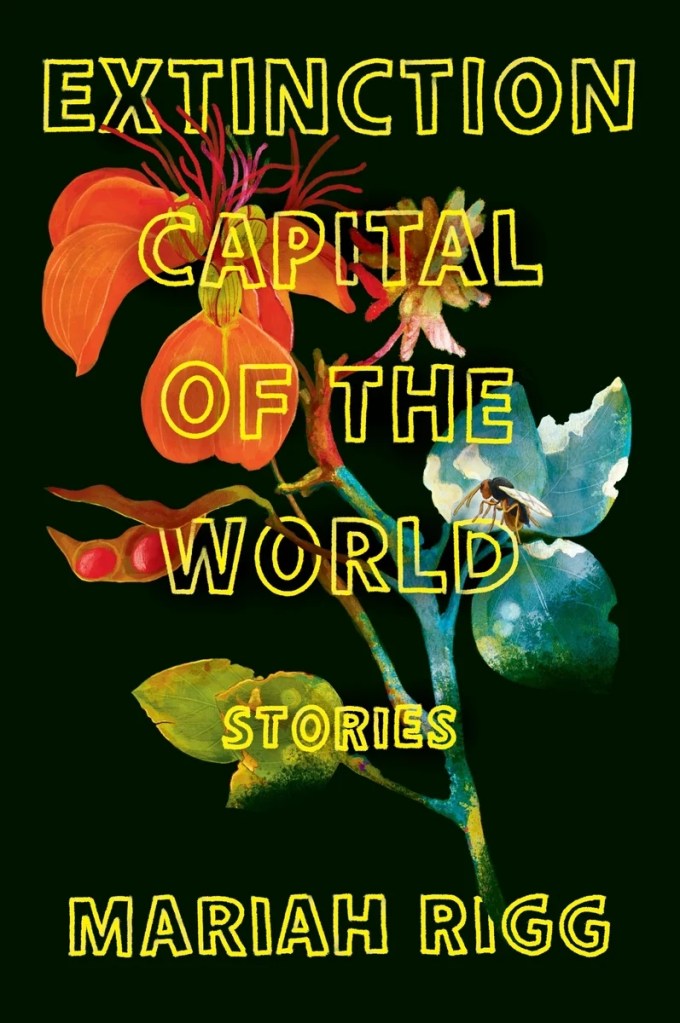

Extinction Capital of the World

By Mariah Rigg

Ecco

Published August 05, 2025