In Gabriella Saab’s The Star Society, not even Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender and a classic case of Hollywood self-fashioning can protect burgeoning starlet Ada Worthington-Fox from the Gestapo.

Born Aleida de Vos to a fascist sympathizer mother who beds a Polizeiführer for her own protection, the pre-professional ballerina and ally to the Dutch resistance escapes her SS-occupied home in Holland to reinvent herself as a British ingénue abroad.

As her big break into total movie stardom nears, she’s reminded by her studio head, Mr. Hendrix, to “be the woman the public expects — elusive, alluring, and a damn good actress. Keep quiet about politics. Make me money. Do that for me, and I will keep you and those important to you safe.” But what Ada soon realizes is that her outspoken Communist yet closeted agent, her established male co-star and love interest, and her studio can only protect her so much. It is not only the usual rabid fans and conniving gossip columnists that pose a threat, but also the suffocating trifecta that is her past, the looming Communist witch hunt, and the reappearance of Ingrid, her twin sister secretly turned private investigator, whom Ada prayed was still alive.

Saab is no stranger to writing WWII-inspired historical fiction. Her latest release ventures into the realm of the Hollywood novel, a genre known to initially seduce its readers by conjuring the elegant ghosts of entertainment’s past. The buzz surrounding The Star Society and the knowledge that Ada’s character is loosely inspired by Audrey Hepburn proves that we still long for a Hollywood that is not our own: a world of glitz, glamor, and mystique that feels unreachable today, given how radically the industry and our access to the private lives of celebrities have changed. Yet, as readers of Hollywood novels going back to Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust (1939) and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon (1941) know, underneath this veneer lies (or, rather, should lie) sustained commentary on the illusions, labor, and corruption that the dream factory is built on.

The Star Society promises an admirable fusion of the wars being waged on Hollywood in the late 1940s — namely, McCarthyism’s anti-communism crusades and the labor wars — with a backdrop of Allied heroics, domestic theatrics, and the chilling assimilation of Nazis into US intelligence organizations as Cold War assets. Yet, despite its loudest power brokers, its publicists’ ability to spin any narrative, and its aura of invincibility, Hollywood cannot shield Ada from the PTSD inflicted by her mother’s Nazi lover or from the government’s misreading of her seemingly vapid “Star Society” soirées.

Entering the public eye only accelerates what is inevitable: Ada’s family will find her and do whatever they can to prevent her from telling the truth. Ingrid, working undercover as her sister’s assistant in an attempt to determine where Ada’s political loyalties lie, arranges an interview with The Dish. Minnie Musgrave, The Dish’s resident gossip columnist, warns, “Law and order don’t exist in Hollywood. Don’t leave your world if you’re not ready for ours, doll.” Musgrave’s message sounds sexier and more threatening than what the novel actually realizes. Outside of the unresolved family issues that ultimately drive the plot, the gravity of its tensions dissipates almost as soon as they appear.

Marketed as thrilling but undermined by its erratic pacing and clichéd plot twists, The Star Society reads like a rock skipping across a pond: skimming the surface of the Red Scare’s threat of contempt charges, industry exile, and federal imprisonment, yet never fully interrogating how gender informed criminalization and incarceration under the House Un-American Activities Committee. The novel skids over promising but peripheral First Amendment issues, the mechanics of star construction, the give-and-take of the industry’s gossip machine, and the sexual politics and queer subtexts that dictate public and private behavior — only to sink into predictable family melodrama.

Where Saab excels is her portrait of the younger Aleida as she spearheads blackout performances at the Muziekschool to raise money to protect Jewish community members, including her beloved ballet mistress, Madame Bellamy. This sole narrative thread, with its exploration of the dance studio as a site of refuge and resistance, could easily sustain an entire novel.

In the end, The Star Society is a novel that privileges breadth over depth, gliding over the promising frictions between gender, politics, and stardom that could have transformed it into a genre-defining work.

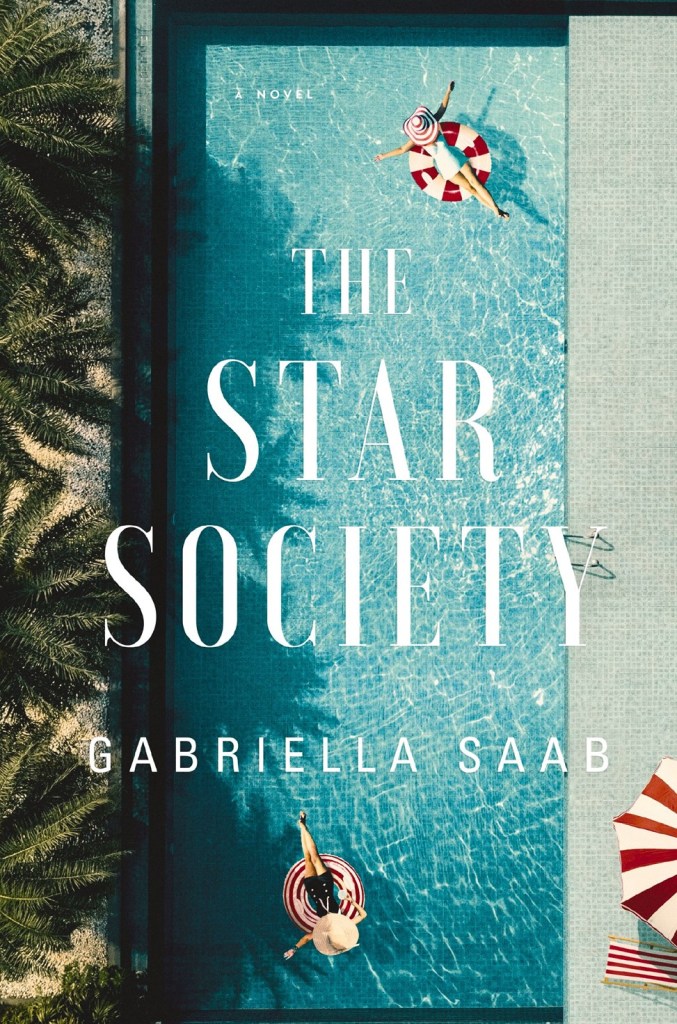

The Star Society

By Gabriella Saab

Harper Muse

Published January 6, 2026