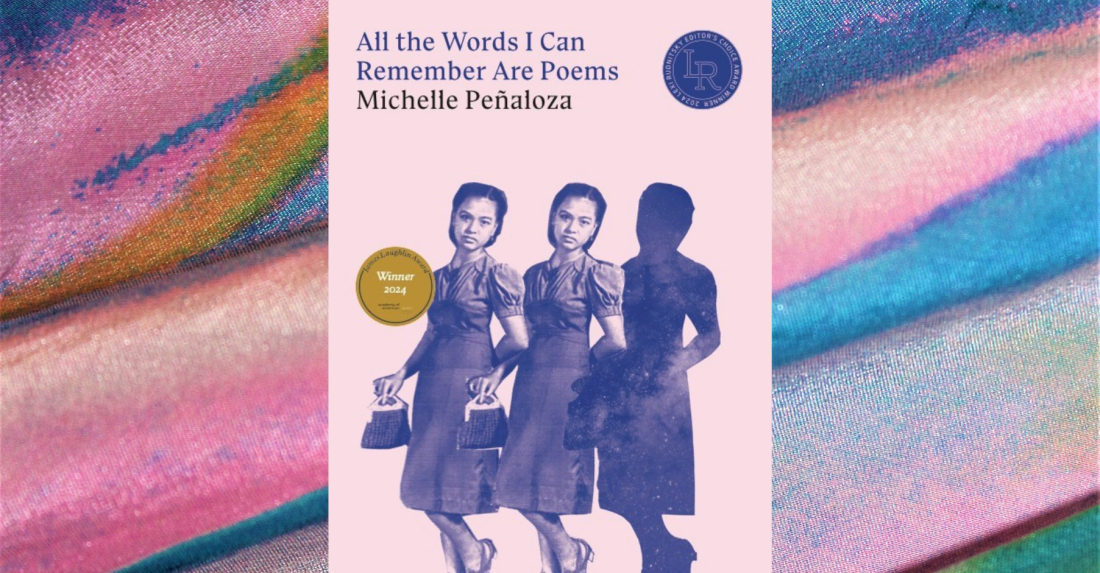

Meaning is dictated by use, isn’t that always the case? Michelle Peñaloza’s second full-length collection All the Words I Can Remember Are Poems reminds us of the function of poems: to record, to remember, to share. Braiding archival images, commercial products and invented forms, Peñaloza’s latest collection emphasizes how new forms don’t supplant or forget existing ones, but offer variation — a kind of play — which is the point of the poem, to make and to make again.

Peñaloza describes the stereograph poem she invents for this collection as a poem “which can be read up and down the two columns, like a newspaper, and also across the two columns, referencing the manner in which the two images of a stereograph would blend together in the proper viewing instrument.” Like Tyehimba Jess’s syncopated sonnets which Jess describes as a way “to stretch contrapuntal to the absolute limits,” Peñaloza’s stereograph poems emphasize the distance between two corresponding melodies. The effect offers a different approach to a record reproduced by an archivist who is both of a place and distant. Much like stereoscopy which presents different images to the left and right eye of the viewer, the stereograph poem requires we see through two distinct lenses. Peñaloza’s form is a way to speak back to empire while also acknowledging what it means to be a colonial-immigrant.

In “Stereograph: After A Typhoon—Wherever The Roof Lands, There The Filipino Makes His Home, 1912,” Peñaloza writes:

All they can see through their little boxes: a choice. We know the importance of

home, removed twice. Indio. Filipino. know-how: how to build many homes

Double-double. Any fool knows a roof not your own, how to ask for nothing.

intact is no miracle, but a blessing of Bubong. Silid. Silong. A music in the

design. What do they know of God’s common sense of our homes. We know

In terms of form, the stereograph poem is “a blessing of / design” (or if we read the poem another way, “A music in the / design.” What it allows the writer and the reader is not a countermelody but a doubling — not a filling or contentful repetition but a doubling of effort: “We know the importance of / know-how: how to build many homes / not your own, how to ask for nothing.” Much like the collages within All the Words I Can Remember Are Poems, these poems address the duality of content and speakers who exist in two distinct but overlapping contexts. One cannot fully occlude or obscure the other, and yet the result isn’t wholeness but displacement.

Peñaloza writes to us as the daughter of Filipino immigrants. To include her cousins in her poems it to include borders, documentation, and the economic overlap of the Philippines and the United States. In “Barangay,” when she writes, “We’ve met. We / rowed a long canoe / from one end of horizon / to another.” I want to know if we’re moving away from home or towards it. On which end is the barangay (a municipal term which, in my own family, is casually interchangeable with home)? This recognition, this displacement gets to the heart of a particular grief. What does it mean to see the part of the whole before the whole? Or to partake only partially in language? In place? In “How Not to Forget,” Peñaloza writes:

Lay on the floor and say aloud the words you can translate in real time:

ganda lungkot kahirapan puso buhay ginto

Listen to your stomach: kumain ka ba? Crave a chili cheese hotdog. Curse being so

far from a Coney Island or a Sonic.

The body becomes both a vessel of intentional and unintentional memory. The speaker houses memorized language (a dutiful effort!) and cravings for American fast food. Essential to my reading of this more personal narrative is Peñaloza’s inclusion of the historic narrative. How, as an American among family, do we acknowledge that a personal history might still reflect a history of occupation. As Peñaloza clarifies in the logic statements of “Standardization,” where “:” might be read as “is to,” “Empire : Diaspora” and “Utang na Loob : American Dream.” Because diaspora is inherently tied to empire, the American Dream always carries a life debt, a gratitude, but to whom do we bestow our gratitude? When Peñaloza writes about utang na loob (the debt of gratitude) we carry in regards to empire, it is not because we owe gratitude to empire.

Perhaps the collage “Hangang Sa Muli,” works to undo this displacement. In the collage, Priam’s birdwing, blue morpho, monarchs, sunflowers, coleus, violets, pansies, and Nasturtium flood the monochrome image of a man smiling. A poem with the same title, “Hangang Sa Multi” begins “We see our dead everywhere.” Like her poems, Peñaloza’s collages create an artificial space for reunion. If one might ask the inanimate objects of the collage where we’ll see them, how might they answer? The butterflies come from Australia, North and South America. The flowers are less clear about their origins. I’m suspicious of their catalog-like sheen, even as they are laid out in an act of care, over a human body. I cannot say if they are native or non-native flowers, because I cannot place the man in the photograph within a particular geography. What is the difference between protection and concealment, and might the hands covering the subject’s body imbue more meaning than the objects which cover the body? The contrast of the monochromatic human face to the technicolor flowers, like the Sterograph, creates two lenses.

When we see these flowers again in “Battlefield near Malabon,” they are overlaid onto an image from 1899 titled “Dead Filipino on the Battlefield near Malabon.” The flowers obscure the body of the dead Filipino. The preceding poem “The Captions Are Handwritten” describes what the collage obscures (in terms of image and historical context):

Insurgent prisoners are prisoners rising in active revolt who have been caught. Insurgent dead are dead people in active revolt.

The crown of the dead insurgent forms an eye that meets the camera’s gaze. His

torso bloats taut. His hands make no sense relative to the location of his head

and his feet.

The photographed dead are “in active revolt,” an ongoing resistance to colonial occupation, which like the bodies of the dead, is also obscured. In the same poem Peñaloza notes “I’ve been down the rabbit hole of this archive many times…You may have noticed I, the poet, have introduced myself into this piece.” She addresses the reader and entangles us in a history we can no longer deny having seen. Within this archive of war images, the audience is, “a consequence of conquest.”

All the Words I Can Remember Are Poems prompts us to react to a chain of events which is still in motion. The reader is “a consequence” in the present tense. As such, what is our relation to the body obscured by flowers? To the curator? The Rofel G. Brion quote that follows this poem, “Bawat katagang naihahabi ko sa tula ay dulot mo” (every word made into the poem is because of you), is inherently in conversation with the title of this collection. Peñaloza’s insistence on proximity without fusion acknowledges the causal arrow of because — of history, of love, of violence. It is the work of the reader to, in turn, acknowledge an inheritance of this “because of you,” and to decide if what we make from this consequence is also a poem.

POETRY

All the Words I Can Remember Are Poems

By Michelle Peñaloza

Persea Books

Published September 16, 2025