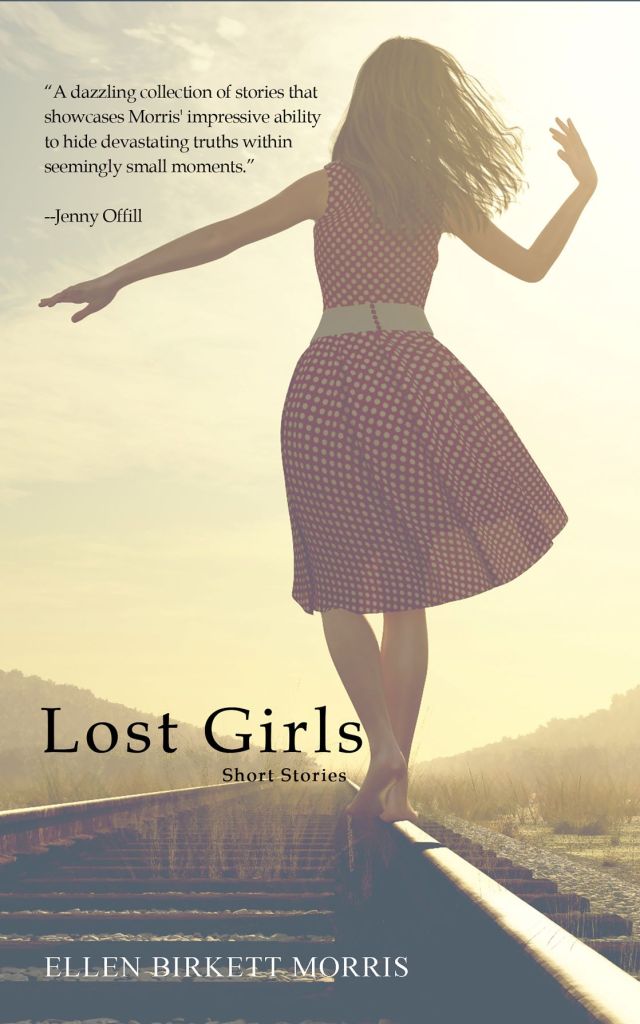

The female characters in Lost Girls both startle and uplift us, but most importantly they demand to be seen. Set in and around the fictional southern mining town of Slocum, each of the seventeen stories in this collection features complex women and girls in pivotal moments of loss, self-discovery, and rebellion. With the same ease found in her Bevel Summers Award-winning short story, “May Apples,” Morris weaves in difficult topics effortlessly. In this collection, she does the important work of showing women as complicated, resourceful, erotic, unlikable, and bold in the face of societal pressures and outright violence against them.

As Morris told the Southern Review of Books in July, these stories were initially intended for a collection built around a male photographer traveling around the South for the bicentennial. “Then the Me Too movement happened,” Morris says, “Women were bravely telling stories and getting taken seriously. I realized my fiction reflected the rape, sexism, ageism, and pressure to conform that was being discussed in the larger culture. I wanted these fictional voices heard.”

While these stories do feature experiences of repression and loss, they do not focus so much on the traumas as the resilience of the women surviving them. A quiet defiance pulses throughout the work. Whether it’s a girl embracing her tummy sticking out, a married woman discovering her queerness, or a young woman taking charge of her life by ending it, these are women who refuse to conform to the expectations placed on them by regional values, institutions, and even themselves.

The book opens with the title story, “Lost Girls,” which despite being one of the shortest, establishes the main themes right off the bat. Based on the author’s personal experience, “Lost Girls” is narrated by a young woman grappling with the abduction of a girl in her community and the connection she feels to the experience even though she never knew the girl personally. As years pass and she reflects on her own fear of disappearing — both literally and figuratively — she develops an annual tradition to privately honor the girl’s memory, speculating all the while, “How does somebody just vanish?”

Female erasure crops up in gradually nuanced forms as Morris explores the different ways women become invisible, whether through kidnapping, violence, or the subtle ways society disregards the female experience. The elderly Abby Linder mourns her youth in “Harvest,” as she reflects on opportunities she missed because she “never planned to be obsolete.” After being knocked down by a teenager on a bike, she seeks solace with her friends. “…[The] ladies cooed over her wounds. Sandy spread salve over her palms. ‘When you get old, it’s like you’re invisible.’”

In one of the most hauntingly realistic stories, “Neverland,” childhood friends Angie and Eileen reconnect after years of losing touch. While looking at an old photograph, Angie recalls the signs of abuse she had witnessed in Eileen’s childhood and her own inaction:

“I mourned the girl in the picture who took the blows and went on acting as if everything was normal. I mourned for myself, for my confusion and complicity, for the way I clung to innocence in the face of the hard reality…”.

Though they never discuss the abuse, an acknowledgement exists between them. Over drinks, Angie reflects on their childhood, “It would stay a Neverland, equal parts innocence and menace, which we survived only to find each other on the other side.”

Female relationships shine throughout this book. In many of the stories, the characters repeatedly find solace in their female relationships. In “A Rumor of Fire,” a young girl flees into the woods after discovering that her father is having an affair. Her best friend, Charmaine, runs closely behind her and helps her set fire to the woman’s clothes. In an elusive ending, Morris captures the camaraderie between the two girls beautifully: “I ran through the woods as fast as I could, hearing the comforting sound of her breath as she ran behind me.”

In “Fear of Heights,” Allison is married to a man when she meets Lydia and falls in love. She leaves her husband to be with Lydia, and her husband condemns her for her lifestyle. Years later, at his funeral, Allison receives a hand-carved rose he left to her. On the way home, “Allison put her hand in her pocket and felt the thorn sharp against her finger. She drew her hand away and placed it on her lap. She was staring out the window when she felt Lydia’s hand find her own.”

Through vivid snapshots of female struggle, Morris demonstrates the power of women acknowledging one another — and themselves — in a world where they are continually diminished. The women and girls in these stories hold the antidote to their own erasure, and in turn give it to us: Only we can prevent each other from becoming lost girls.

FICTION

Lost Girls: Short Stories

By Ellen Birkett Morris

Touchpoint Press

Published June 24, 2020