Tiana Nobile is a Korean American adoptee poet, Kundiman fellow, and recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award. A finalist of the National Poetry Series and Kundiman Poetry Prize, she is the author of the chapbook, The Spirit of the Staircase (2017). Her writing has appeared in Poetry Northwest, The New Republic, Guernica, and the Texas Review, among others.

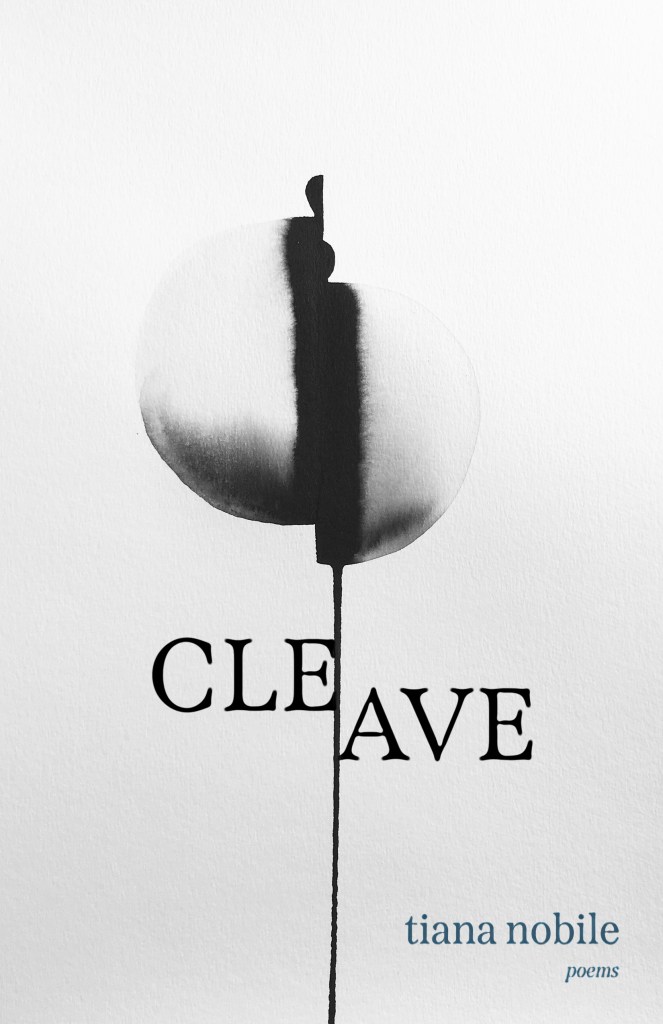

Henry Goldkamp recently spoke with her about her full-length poetry debut, Cleave, out now from Hub City Press, which explores the science of love and attachment through the lense her own transnational adoption from Korea.

For the title of your debut collection Cleave, you choose a linguistic rarity known as a contranym, or Janus word: a slippery sign that denotes both one meaning and its opposite (others include “buckle,” “dust,” or “rent”). You make clear the vacillatory nature of dueling signifiers in your poem “The Stolen Generation”:

The word "cleave" means both to cut and to cling.

The child cleaved to her mother The child cleaved from her mother

The difference a word makes in the forest of our longing.

The context of desire, then, draws the word’s meaning here. How does this “contranymity” enter into your poetics as a Korean American adoptee, this experience serving as the keystone of the collection?

As a Korean adoptee, I’ve often felt like I was being pulled in opposing directions. Being raised by white parents in a predominantly white town and going to white, conservative Catholic schools, I was told “You’re just like us!” by my family while elsewhere receiving the message that I was an alien. It was also extremely confusing to feel both loved by my adoptive family and rejected by my biological family. It’s like when you try to push magnets with the same poles up against each other, and you just, can’t. They repel each other because they’re the same. Words and concepts like “cleave” perfectly capture this feeling for me, linguistically. There’s both a tension and a sort of equalizing that happens. They helped me begin to accept the idea that I / my poems don’t have to choose one or the other. We can be both, and.

So the body serves as a kind of haunted house: ancestry, dreams, childhood, electricity all packed into some bit of flesh, the human uniform of the spirit.

There are studies that investigate the passage of trauma across generations, and there’s evidence that suggests it’s possible for us to carry the psychological wounds of our ancestors in our DNA. I think of my body as a kind of vessel holding the specters of my mother’s and grandmother’s trauma. As an adoptee, that has manifested as a kind of haunting. The identity of my biological family and the circumstances surrounding my birth were a mystery to me for most of my life, and yet they have indelibly impacted who I am and how I navigate the world.

I hold the trauma of my unwanted conception and the consequent rejection by my biological family in my body. I see it manifest in bouts of severe anxiety and compulsions like trichotillomania. On the other hand, I also think it’s made me a curious introvert and a deep empath. Writing poetry (and years of therapy!) gave me an entry point into understanding these ghosts that live in my body-house. It helped me to at least attempt to decipher such haunted messages.

Not only does hair-pulling twist itself again and again in Cleave — cheek- and tongue-biting also recur prominently. From “Child’s Pre-Flight Report”:

Speaking Ability: She will learn quickly when to bite her tongue.

For years, she will hold it tightly, teeth clenched.

In her mouth, the bitter taste of a broken

bloodline.

Transgenerational trauma, then, as emotional suppression, as silence, but a kind of learned social performance as well. An invisibility which festers in itself, eating its own blood.

I don’t think of it as emotional suppression per se, but more like an unwrapping of the various layers of the self. This work is endless, though, isn’t it? I feel like I discover new fears, anxieties, and pleasures every day. And they change constantly. Re-dress themselves. Wear different masks.

Cleave disrupts this American mythos of childhood innocence. I’m thinking, too, of how you relay the adoptive trauma trans-species from your research into Harry Harlow’s controversial experiments, in which he separated rhesus monkeys from their mothers and provided inanimate surrogates in their stead: “Monkey in the cage, pulling out her hair, / waiting for someone to claim her” (“Abstract” p.15). What did your research of those experiments open up for you and your creative process while putting together this collection?

I think it was in 2010 when I discovered the blog, “Harlow’s Monkey: An Unapologetic Look at Transracial and Transnational Adoption,” written by JaeRan Kim, a fellow adoptee born in South Korea and raised in the US. This blog introduced me to Harlow, his monkey experiments, and the science of love and attachment. At the time, I was just beginning to think deeply about adoption — both my own and the larger adoption industrial complex — and this blog set me on a path to understand the history of attachment theory and how it informed my own self-development and lived experiences.

At first, the Harlow experiments provided me with a springboard to consider hard topics like loss and separation from a distance. From here, I also began to research instances of mass adoption, such as Operation Babylift in Vietnam, Operation Pedro Pan in Cuba, The Stolen Generation in Australia, the Sixties Scoop in Canada — the list goes on. It was both illuminating and horrifying to learn about such patterns throughout history and then to recognize parallels today, such as the US sanctioned family separations that continue to happen on the border. This “take the children” strategy finds its roots in slavery and imperialism; cutting children off from their families kills a culture, erases familial identities, and expedites assimilation into whiteness. This message then gets ultra-simplified and translated into “save the children” rhetoric to make it more palatable for the general public. Ethiopia actually banned foreign adoption in 2018, officially acknowledging the potential for harm. In the 90s, the president of South Korea issued a public apology to international adoptees for not being able to take care of us.

Learning about Harlow and the history of adoption helped frame my exploration and enabled me to consider where my story fits in context and take the vulnerable step to write more autobiographically.

The afterbirth of your research often appears as questions in this collection. “What is the opposite of mother?” (“Abstract” p.15); “How much can you learn / from a stranger’s surname?” (“Moon Yeong Shin”) or your poem entitled “Where are you really from?” So, a question on question marks: what place does eroteme (the schmancy word for ?) have in your poetics?

For me, the act of writing the poem is a type of interrogation. Very often, as you point out, that act provokes more questions. That’s also why research plays such a prominent role in my writing. One question almost always leads to another, and following that line of inquiry can be thrilling. Sometimes — most of the time? — the poem doesn’t answer the question. Instead, it spirals, pokes holes, turns in on itself.

I’ve learned so much by starting with a question. About myself, my relationships, social and political histories. As an Asian American person, the question, “Where are you really from?” can often feel hostile and is rooted in the racist idea of Asian as inherently foreign. At the same time, it’s a question I’ve personally grappled with throughout my life as an adoptee of color. The act of writing Cleave began as an exploration of this seemingly simple yet very loaded wondering and led to more questions. Like: Why was South Korea one of the highest exporters of children in the 1980s? How do South Korea and the United States benefit from such an exchange? What is the history of transnational and transracial adoption, and in what ways is it informed by international politics? How is my adoption connected to larger systems of colonialism and power?

A testament to your adroit ability to ask questions, as these are incredibly important, complicated answers.

There is such a dearth of adoptee stories out there told from the perspective of the adoptee. Even less from the biological family. Most adoption stories are narrated by adoptive parents and adoption agencies. This is problematic because it centers the savior narrative over the people who are most directly impacted. To shift the narrative to center the adoptee is a radical paradigm shift. However, like many adoptees, the beginning of my story was blank, which makes it difficult to know where to begin. So I began with questions.

Do you consider Cleave a kind of taking back of the ethnocentric “savior narrative” you describe above? I’m thinking especially of your poem “To Whom It May Concern:,” which disrupts a letter “authoriz[ing] Mr. and Mrs. to baptize their daughter .” And also “Child’s Pre-Flight Report,” whose first section begins with bureaucratic fact-filling, a hybrid found poem in which the last box reads, “Destination: Unknown.”

Both forms (poetic form and government paperwork) remind me very much of Harlow’s surrogates, a kind of contrananymous light. Yes, the false-mother is warm, but fluorescent, wooden, bloodless… These are cold inventories, but in poeticizing them you give them the warmth of the Real.

Discovering these forms was a significant moment for me, personally and poetically. Like I mentioned earlier, while they answered some questions, they also led me down new rabbit holes. Using them in my poems opened things up for me in multiple ways: it enabled me to take some agency over the telling of my own story/history, and it gave me space to grapple with what’s both there on the page and what’s missing. In some poems, I tried to elevate the absence through silence, highlighting the white space on the page. In others, I experimented with myth-making by re-imagining and constructing an origin story that was entirely my own.

Images of stone or rock appear frequently in the collection, and with them a surprising vitality not often associated with rocks. This stanza from “What orchard are you from?” transitions these two elements:

Take me by the jowl,

the stony pit

I keep buried in my mouth.

In another poem, “Abstract” (p. 35), you conjure a world in which rocks are fire: liquefied, melting, “endlessly moving.” Finally, you challenge the noun with the ultimate motion of motherese:

She made her bed with broken glass and stone. [...] Isn't this the cost of being alive? You challenge yourself. You rock yourself to sleep. (St. Rose of Lima)

Many poems in Cleave disrupt at their metaphorical faults, and while the result isn’t a landslide exactly, there is a gradual cleft by the end of your collection — at once satisfying, soothing as a mother, and irrational and unruly as the infant she rocks.

Part of the job of a poet is to disrupt lexical expectations. To unearth meaning, subvert it, and re-present it. This is one of the reasons I have a huge fascination with erasure poetry. Voyager by Srikanth Reddy is one of my favorites. In it, he uses the memoir In the Eye of the Storm by Kurt Waldheim as his base text and reinvents it — content, style, tone — it’s absolutely brilliant. Waldheim was a former UN Security General and served as an SS officer during World War II, a fact that is absent from his autobiography. Somehow, Reddy manages to uplift and point to these inherent silences and construct not one but three entirely original narratives, all while using Waldheim’s own words. Philip Metres does similar work in his book, Sand Opera. Books like these greatly inform how I approach my work not only as a poet but as a witness and documentarian.

Metres describes some of his primary concerns as both “erasure… and how fantasy projection actually destroys the sovereignty of what is.” To de-story the status quo aligns with your own poetics in Cleave. In your poem “/mun/,” a single line extends these ideas into what might be considered an ars poetica of erasure: “Sometimes lesser splendor reflects fits of frenzy.”

For my dictionary poems (“/ˈməT͟Hər/,” “/ˈmīɡrənt/,” “/mun/,” and “/ˈməŋki/”), I incorporate text from the Oxford English Dictionary. It’s not a pure erasure, but it’s a kind of collage of found text mixed with original language. In writing them, I wanted to get as close as I could to each word, to engulf myself in their meanings. The Argentine poet Alejandra Pizarnik often wrote about language as inherently limited by its inability to capture the full essence of a thing. Like the word “apple” will never be an actual, tangible apple, right? There’s this fundamental distance between the word and its object. The question remains: does that point to the failure of language? Is it a word’s job to instantly conjure? How can we get close enough? What’s enough? As a poet, I can’t resist trying, even if I know aspects of it will inevitably elude me. Once I feel like I have a grasp, I’ll flip it. Ask it questions. Plant it in the garden and see what grows. Perhaps that’s why a word like “cleave” felt so perfect. Once you think you have it, it slips out of your hands and changes its clothes. It keeps you on your toes.

POETRY

Cleave

By Tiana Nobile

Hub City Press

Published April 6, 2021