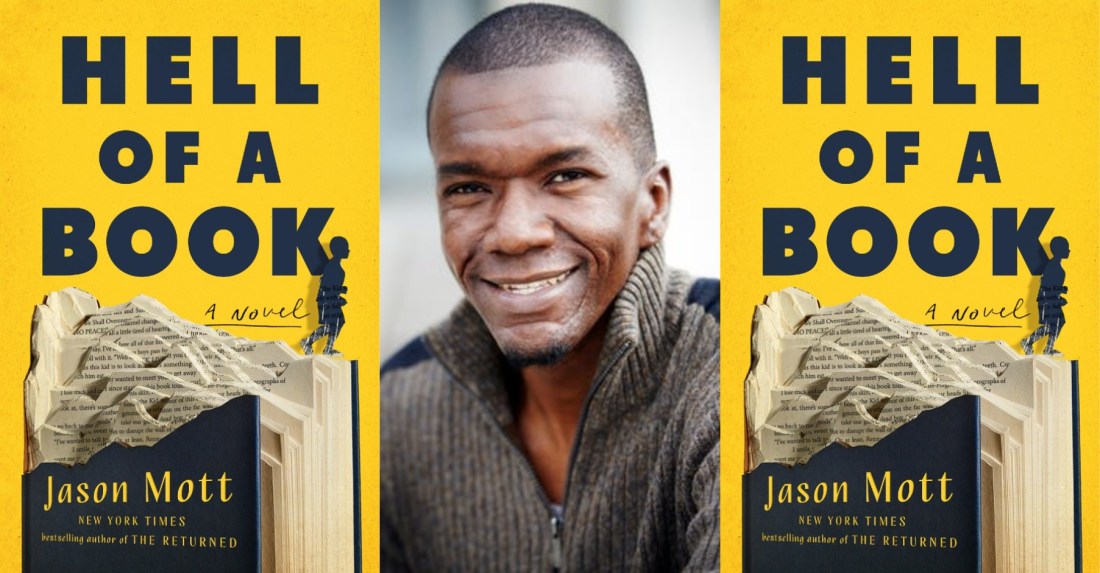

At a memorable low country dinner following his December 2018 onstage conversation with fellow New York Times bestselling novelist Wiley Cash, poet and fiction writer Jason Mott shared an absurd but nonetheless true story of how he once had to switch clothes with his photographer during an author photoshoot. It was one of several stories he recounted that night from his outlandish experiences on book tour and amid the curious business of American authorship.

Mott earned his BFA in fiction and MFA in poetry from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, where he has been the Writer in Residence. He is the author of two poetry collections, We Call This Thing Between Us Love and “…hide behind me…” He is also the author of three novels, The Crossing, The Wonder of All Things, and his debut novel The Returned, which was adapted for a television series as Resurrection.

His newly released fourth novel, Hell of a Book, uses some of the unreal experiences from his life as an author as a framework for a powerfully envisioned and artfully crafted exploration of identity and love (in their many forms), and of the unrelenting perils of being Black in America. Mott masterfully weaves together two seemingly disparate narratives — one a fantastical book tour for an unnamed author, the other an all too familiar story of police violence in a Black community — into a labyrinthian surrealist tale that is by turns farcical and heartbreaking, tragic and redemptive.

In our interview, Mott talks about his inspiration for this braided narrative, the challenging but rewarding balancing act of the novel, his deep gratitude for his readers, and the inspiration for Nic Cage’s cameo appearance in Hell of a Book.

E. L. Doctorow said, “The nature of good fiction is that it dwells in ambiguity.” Hell of a Book is a book of questions (so much so that it ends with one) for which the reader is left to fathom the answers. What were the big questions of this moment in our fraught American experience that prompted your initial foray into this narrative?

There are a lot of things that began this narrative. Maybe even too many to list! But I’ll try to boil them down a bit. Essentially, this story began as a way for me to explore my thoughts and feelings on life as a minority in America, specifically, a Black male in America. While the scaffolding for this novel — the author on book tour format — was built long ago, it wasn’t until about two or three years ago that I finally decided that I wanted to write something which would try to engage with the complex conversation of America, race, and the police. Yes, the novel is mired in ambiguity, but only because I believe writers should be philosophers, and the thing that good philosophy does is not answer questions. Instead, I believe that good philosophy does the work of raising good questions. That mindset was the basis for much of the ambiguity found in Hell of a Book.

With chapters alternating from chronicling the book tour adventures of a nameless Black American author and following an ill-fated ten-year-old boy nicknamed Soot (because of his very dark skin) who may or may not be able to disappear into the Unknown, Hell of a Book uses absence — being unnamed, unseen, untethered — to question the very notion of a knowable identity. Whether within or beyond the book, is it possible to truly know oneself? Or anyone else?

I think knowing one’s self is a perpetually moving target, and that often gets overlooked. We are not now who we once were. Each day we’re growing and evolving — hopefully — and so knowing who we are requires constant self-reflection and pushing of boundaries. It’s possibly the most difficult thing a person can do over the course of their lives. So, getting to know others becomes something infinitely more difficult. Yet, we all have to try. That might be the most important thing we can do with our lives: truly try to know others.

The relationship between the Author and the Kid, the young Black boy whom the Author alone can see throughout the book tour, consistently defies easy categorization, but always serves as a reminder that the Author is uncertain of his reality. Do you find this to be true in your own creative life as well?

Definitely. Ha-ha! At this point in my life, I’ve been writing fiction for so long that I often feel like I do struggle to know where my realities and my imaginings begin. But I think that’s a good thing. Frankly, it’s a wonderful place to be because my imagination helps me process my reality. So that’s certainly one thing that I’m glad to have in common with Hell of a Book’s author character.

You may not remember this, but we talked a bit about the genesis of this book when you visited Beaufort several years ago. As I recall, at that point, you were considering a memoir chronicling your own bizarre experiences on your book tours. How did you get from that premise to this surrealist novel with its interwoven storylines?

I actually do remember that conversation. This story has been building for a while. The end result that culminates in this novel isn’t as far removed from reality as you might expect. There is more memoir and autobiography in this novel than most people suspect. But when I was working on this novel, I wanted it to have an impact similar to expressionist art. I wanted to capture the feelings of book tour more so than the actual reality of book tour. So, what I would end up doing was taking parts of my own story and adding in just enough surrealism and absurdity to make them evocative and, at the same time, relatable for the reader.

How did you make it through this novel’s expedition into the often-ridiculous business of authorship without telling the story of how you swapped clothes with a photographer for your earlier author photo?

Ha-ha! Well, I gotta save some stuff for future projects!

I predict much debate among book clubs and critics for years to come over where the Author ends and Jason Mott begins, but one place you unquestionably overlap is in adoration for Nicholas Cage, who has a profound cameo in the novel. Why is Nic Cage essential to this narrative? And who wins in a street fight: Cameron Poe, Castor Troy, Memphis Raines, or Spider-Man Noir? (To make it fair, Big Daddy and Johnny Blaze will sit out this rumble.)

I love this question so much! Ha-ha! Yes, I’m a longtime Nic Cage fan. I honestly can’t remember not being a Cage fan. But I think he connects with this story more than most people suspect. So much of Hell of a Book is about identity. Both the way we see ourselves, and the way others see us. And part of why I’m such a Nic Cage fan is because I believe that he has an ultra-sharp sense of how others see him. He’s aware of who you think he is and, because of it, he’s able to lean into that expectation or subvert it as his whims dictate. And somewhere in the middle of all that, I feel like more than anyone, Nic Cage owns his identity. And that is something I always have, and always will admire.

As for your other question, I’m gonna throw in another Cage character and say that Red Miller from Mandy wins any scrap that might come his way.

Hell of a Book interrogates the expectation that Black writers must tell Black stories, or, viewed through a wider lens, that artists of color must respond to themes of race in their art. And yet this novel is, in overtly candid and unsettling ways, a deep dive into the precariousness of being Black in America. In the arc of your writing life, certainly including your early works of poetry and prose, how have you navigated this expectation? As responsibility, obligation, burden, opportunity, or something altogether different?

This is another great question which lends itself to a rather fluid answer. The fact is, nearly all minority voices are burdened with the expectation to be “ambassadors” for their communities to the larger majority. This is something I’ve tried to navigate all of my life. There are moments when it becomes a suffocating, oppressive voice that threatens to drown my creativity and whatever self-identity I might be exploring. I think this is one of the greatest dangers of this type of paradigm: minority voices are always smothered by expectations placed upon them by the majority.

So, yes, “burden” is certainly one of the best words to describe it. Can it become something else? Maybe even an “opportunity?” Perhaps, but I would argue that the cost is too high.

The tonal balancing act of the novel is extraordinary. It traverses terrain that is comedic, heartrending, scathing, and optimistic, and yet always unified, always in service of the story. Can you explain the magic trick? How did you achieve this balance?

First off, I’m really thrilled to hear that you enjoyed the balancing of this book. It was a particularly challenging aspect of writing it. As for how I did it? Well, that would take more time than I think this interview allows. Ha-ha! But I will offer this: much of the trick to balancing this story for the reader was also about balancing this story for myself as well. There are heavy, difficult moments in this novel and, as difficult as they are for the reader, they were equally difficult for myself as the writer. Perhaps even more so at times. So, when I was writing, I would trust my gut as a metric for when I was getting exhausted and needed a laugh, or simply needed to write something lighter for a while. And I used that to help me get a sense of when reader might also need to “come up for air,” so to speak.

The pithy, snappy, often rapid-fire dialogue is quite an achievement as well, reminiscent of the pacing of 1940s and 1950s cinema. Is that actually your influence? And why is that pacing important to this story?

That was exactly my influence. I’m a big fan of the film noir genre. I’ve got a pretty decent DVD collection of those old movies. I love them because of their singular use of language. There’s a special combination of slang, cadence, and timing in that genre that isn’t present in any other. I wanted to lean into that for this project because I felt the style of it could give this story a unique feel that was missing in other novels that might fall under the same umbrella. Also, it was important for me to create something that was expressive and different. People don’t often think of Black authors as being film noir fans and absurdists, so I wanted to lean into that to show that there is space for Black stories to exist in spaces and with styles we’re unaccustomed to.

One of the lessons imparted to the Author during his media training is that, “You need to connect with your readers at every opportunity.” Pat Conroy did this better than anyone I’ve ever seen. He genuinely wanted to know and thank his readers on a deeply personal level, which is why his signing lines were five hours long. With seven published books of poetry and prose to your credit now, and New York Times bestseller status, what would you most like to say to your own readers in closing?

Like any writer, I’d like to thank my readers. Reading an author’s book is such a powerful and intimate gesture that it surprises me whenever someone does it. It’s very humbling that people would give up their valuable time to listen to a story I have to tell. So I’m perpetually grateful for that and want to thank everyone for joining me in my imaginary world(s). It gets lonely in here sometimes, so it feels good to have others to share these waking dreams with.

FICTION

Hell of a Book

By Jason Mott

Dutton Books

Published June 29, 2021