New York Times bestselling novelist Grady Hendrix has earned a reputation and corresponding loyal readership for his genre-bending approach to modern horror in books like My Best Friend’s Exorcism, Horrorstör, and last year’s The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires. Hendrix’s newest novel, The Final Girl Support Group, asks what happens after a horror movie ends, and answers with an empowering novel of perseverance – with a healthy infusion of humor and a splattering of gruesome nightmare fuel as well.

The Final Girl Support Group interrogates the culture of violence against women through scenarios adapted from iconic slasher franchises, from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to Scream. In Hendrix’s novel, six “final girls,” once the intrepid teenaged survivors of horrific massacres, continue to gather together years later to process their respective traumas. That is, until someone starts killing them.

In our interview, Hendrix discusses how his pandemic experiences helped shape his newest horror story, what his novel has to say in response to the source material that inspired it, how his Southern childhood helped shape his worldview, and which women in his own life have inspired the tenacity of his final girl characters.

When did you begin your immersion into all things horror? Was your point of entrance films, fiction, or a bit of both? And as a writer, when and why were you compelled to craft horror stories?

When I was a kid, we lived in England for a year, and in the library of the house we rented I found Folklore Myths and Legends of Britain put out by Reader’s Digest. It was full of pictures of men dying in gibbets, women being hung as witches, horrifying ghosts, gruesome torture, awful monsters — you know, for kids! After that, whenever we’d go to the library, I’d try to find more of the same. Alfred Hitchcock anthologies like Monster Museum became my drug of choice until I was old enough to start renting horror movies with my friends. After that, it was all downhill.

In terms of writing horror, I always just kind of wrote what I wrote, and when I realized that my horror stories were what people liked best, I doubled down.

Your new novel explores trauma, coping, mourning, isolation, risk assessment, trust, and re-entering society after life-altering horrific events. While this story was years in the making for you, it seems decidedly relevant for this moment when the world is wondering what happens after a pandemic ends. What do your final girls have to teach us about how (or if) one goes from surviving an ordeal to living a fulfilling life again?

I rewrote the entire back third of The Final Girl Support Group while I was in Charleston last August taking care of my mom, who’d gotten sick. While the pandemic’s second wave swept the country and thousands of people died daily, I holed up in her guest bedroom and wrote Lynnette from her agoraphobic, paralyzed existence to a better place. Getting her over the finish line did a lot to get me sane during that summer, and what it made me realize is that final girls survive not because they’re stronger, or faster, or better equipped to deal with tragedy, they survive because they just don’t quit. It’s that simple: the way to make it to morning is to keep going until the sun comes up. It’s not glamorous, it’s not particularly heroic to see, but there is no other way.

Your protagonist Lynnette Tarkington is a paranoid survivalist, and therefore also an unreliable narrator. Lynnette is different from the other members of her support group in that she’s also facing imposter’s syndrome because she didn’t actually overpower or outwit her attacker, or even escape from him. What can you tell us about the origins of Lynnette’s character and how you decided this would be her story to tell?

If I was ever in a slasher movie, I’d wind up as Lynnette. Some maniac with a machete tries to murder me in the woods and manages to kill all my friends, you can bet I’m learning how to shoot, getting a concealed-carry permit, putting triple locks on my doors, and figuring out an escape route from every situation. Of course, like Lynnette, the second I actually put my plans into action they’d immediately fall apart. Because she’s basically me, I found her incredibly easy to write. It’s always fun to tackle characters who have a point of view based on a rigid adherence to a set of inaccurate facts.

Your final girls are significantly more diverse than their on-screen counterparts in the source material. Why was that important to you and to this story?

I like to write about the world I see around me, and that’s a world full of people who are different genders, sexual identities, and ethnicities than mine. I also wanted to rectify some horror movie oversights. It’s ridiculous to me that there’s never been a Black final girl, so I decided there had been, she’d just been whitewashed in the movies. I thought it was pretty likely that some final girl had gotten a spinal injury and had to use a wheelchair. I figured that if someone had been using my dreams to try to murder me, I’d be self-medicating with booze and pills, too. And I think getting chased by a family of redneck cannibals in Texas gets a lot more interesting if the woman they’re trying to catch, kill, and eat is Latinx.

You make clever use of “found documents,” incorporating doctor’s notes, news articles, movie summaries and reviews, and social media comments to augment the primary narrative. That’s been a part of horror fiction since Dracula, and maybe before that. These documents sometimes add credibility to the perspective of your unreliable narrator, but they also let us check in with the world. And that starts to shift culpability for the violence of the novel and the traumas of the final girls from just their attackers to a larger circle of perpetrators and perpetuators who engage vicariously and profitably with these murders after the fact. Why augment your narrative in this way? And in the world of the final girls, who is ultimately to blame for what happens to them?

Horror is the one genre that says it’s true. I mean, there’s no such thing as a found footage rom-com, right? I love my books to have extra bits in them that round out the world and I created so much of this material while writing the book to explore different character’s points of view that it felt like a shame not to use it. And you’re right that it does tap into a cruel aspect of humanity, which is our love of rubbernecking at car accidents. The way we turn some crimes into circuses, shining spotlights on the victims and forcing them to dance, turning their perpetrators into celebrities, turning trauma into trivia. That can’t be healthy for the people trying to put their lives back together in the wake of actual violence. For every victim like Elizabeth Smart, who turns her celebrity into a way to raise awareness and reach out to other victims, there’s someone like Lorena Bobbit who has her life destroyed. The interstitials gave me room to raise some of this without turning it into the central focus of the book.

In terms of who’s to blame for what happened to the final girls, that’s easy: the killers. They’re the ones who started it all, and even though a lot of regrettable stuff happened after that, I think it’s important not to let the blame get too diffuse.

As a horror fan and creator, what can you tell us about why generations of readers and movie-viewers have been drawn to stories of murderous violence and those few who survive to tell the tale? As audiences, as a culture, what are we collectively looking for in these stories?

I don’t know what we’re looking for, but man, we like to write about murder. From sixteenth-century true crime songs complete with gory woodcuts, to Jack the Ripper fan fiction, murder ballads, True Detective magazine, and urban legends like “The Hook,” we’ve been turning murder into entertainment for hundreds of years. I think we’re fascinated by death because the one thing all of us have in common is that we’re all going to die, and who knows what happens next. But I sometimes wonder if this obsession is entirely healthy.

You grew up outside of Charleston, in the once adorable and increasingly sprawling hamlet of Mt. Pleasant. That small town has also been the setting in two of your novels. But beyond that, how do those Southern beginnings play into your writing life?

When I started going to the downtown branch of the Charleston County Public Library, it was still shaped like a fairy tale castle, painted Pepto Bismol pink, with battlements and turrets and I loved it. Around the time I turned fourteen, I learned why it was a big pink castle. Back in 1822, a freed slave named Denmark Vesey had either organized a slave rebellion, or was framed for organizing a slave rebellion, and was executed. Charleston’s white residents were so freaked out that they had to build a fortified arsenal to reassure themselves that they were safe from future slave rebellions. And in 1960 they painted that arsenal pink to make it seem less racist and turned it into the library. It taught me that everything had a secret history and there are unseen forces shaping our world, whether it’s history, economics, or racism. That was a pretty crucial lesson that made me the writer I am, and I’m not sure I would have learned it that early if I wasn’t from the South. Our relationship with our history is fraught, and in a city like Charleston so many contradictory historical symbols are piled up on top of each other that if you learn to read them you start to see a really interesting story where they intersect, like the fact that a statue of Denmark Vesey stands in Hampton Park, named after Wade Hampton III, our governor who was elected during Reconstruction in one of the bloodiest elections in American history, that saw 146 Black people murdered to keep them from voting.

I had the gratifying experience of reviewing your novel for the Charleston Post and Courier with my teenage protégé, Holland Perryman, who got not one single horror film reference in your book. She asks, what novels or films you would recommend for someone new to the genre but keenly interested (thanks to your novel) in exploring that landscape?

There are a few ways to go. My favorite slasher is Black Christmas because it’s a combo of cozy Canadian Christmas cheer and a genuinely terrifying killer. Plus Olivia Hussey’s sweater game is on point and Margot Kidder is a fabulous, hard-drinking best friend. The best franchise slasher, in my opinion, is Friday the 13th Part 2 because baghead Jason is the best Jason and it becomes totally harrowing as it goes along. Plus, it has a super-cruel opening that inspired my book. For a “so bad it’s good” slasher, Slumber Party Massacre can’t be beat. It’s directed by a woman and written by famous feminist author, Rita Mae Brown, so its female characters actually feel like human beings, it’s got some great shots and sequences, and there’s a whole subversive take on male sexuality.

InThe Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, your protagonist Patricia Campbell is the first of her group to fully recognize the dangers they face collectively, but no one believes her, and she’s ostracized as a result. Lynnette is likewise dismissed, and then later suspected, by her support group as the realities of their precarious situation start to be revealed. Are these parallels intentional? What draws you to these characters who must stand alone and prove themselves before they can rally others to their just cause?

I think everyone can identify with the experience of trying to get people to listen to you and being ignored. I feel like I spent most of my teenage years being ignored, so it’s definitely something that resonates for me. In the bigger picture, whenever something horrible happens, like the COVID-19 pandemic, or the 2008 financial crash, afterwards you hear that so many people were shouting warnings and trying to stop it in advance and no one listened. So I spend a good portion of my day worried about what warnings we’re currently ignoring that are going to lead to the next massive crisis.

Both The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires and The Final Girl Support Group show us what a group of empowered, resourceful, and resilient women can do when they trust one another and work together toward a common goal. Are there women in your life who inspire this message?

So many, but in this book I really drew on my older sisters. I grew up with three of them, and they’ve all come riding to my rescue at some point or another, and final girls definitely have that big sister vibe. Also, my wife is a chef, and when she opened her restaurant she was all alone and really felt like she was out there in the cold by herself. She reached out to some other female chefs in New York and they’ve formed a really tight network. They’re a motley crew, but they’re enormously supportive of each other, and seeing how much they have each other’s backs was definitely an influence on this book.

Here’s a big question, in closing: How does one critique narratives that risk perpetuating a culture of violence against women without also adding to that culture as well?

It was really important to me to write a book about violence that didn’t celebrate violence, so I was very careful to make sure that when any of my main characters pulled a gun it wound up making the situation worse and that when they had physical fights they generally got their butts handed to them. It also informed Lynnette’s arc. She starts out as this weaponized woman who imagines herself the baddest bad-ass in town, ready to draw down and punch the ticket of anyone who threatens her, and she winds up rejecting all that and taking the far braver route of trying to save lives however she can.

We tend to celebrate the perpetrators in our world. We can all name Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer, but we can’t name one of their victims. We remember school shooters, not the people they shot. We valorize taking lives and fighting, but we ignore the harder and, I think, more heroic work of raising kids, taking care of aging parents, and saving lives. The stuff that requires more patient effort, the stuff that doesn’t look good framed against the sunset with strings swelling on the soundtrack, but it’s the stuff that holds our world together.

Thank you, Grady.

FICTION

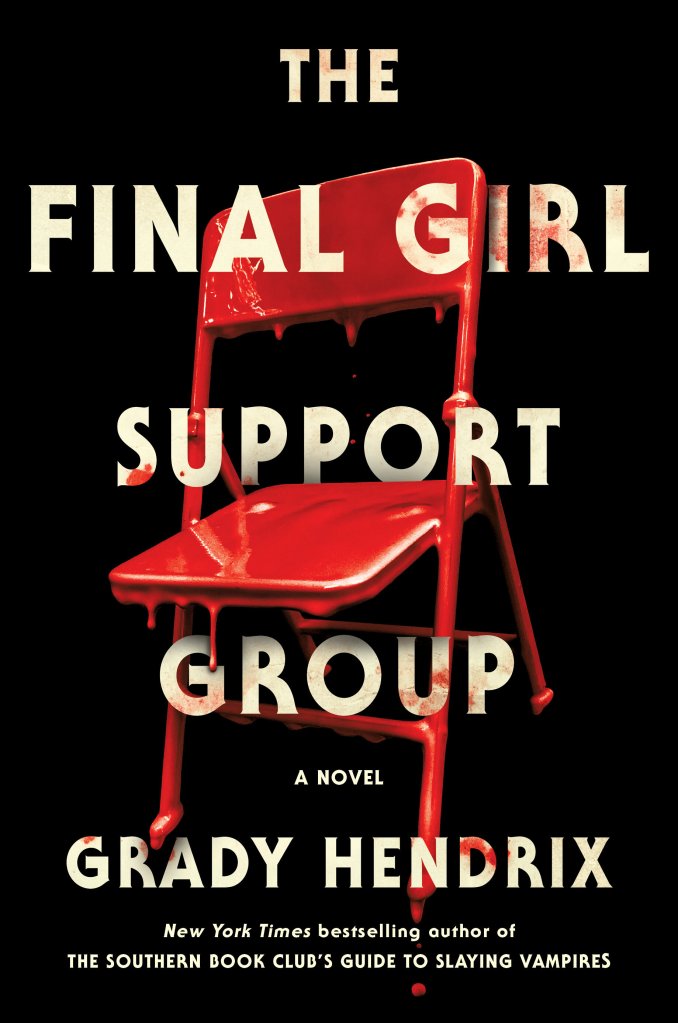

The Final Girl Support Group

By Grady Hendrix

Berkley Books

Published July 13, 2021