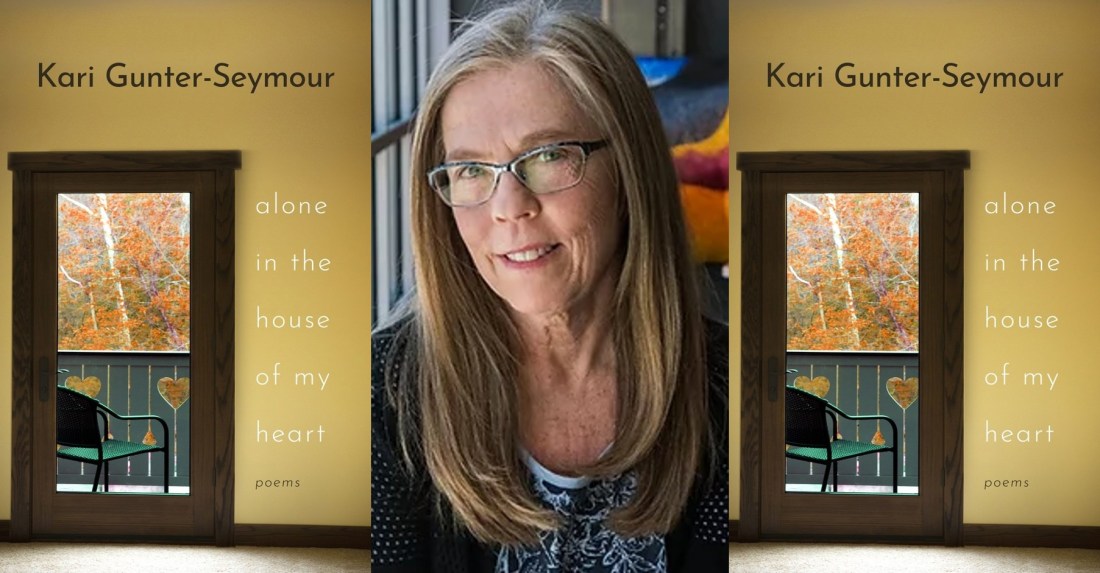

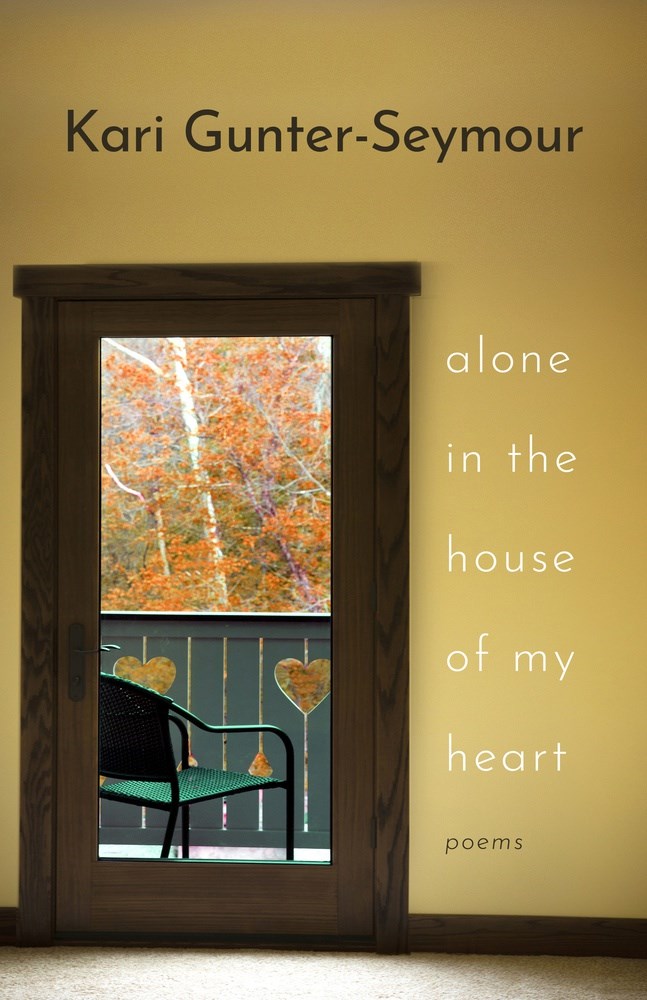

Ohio Poet Laureate Kari Gunter-Seymour’s new book, Alone in the House of My Heart, feels like an invitation to pull up a chair at her kitchen table and stay awhile. In precise, compelling, and melodic language, she draws you into conversation with both timeless and current themes, such as aging, death, COVID-19, and social justice. Gunter-Seymour tenderly frames this collection with her unabashed love of the land and people of Appalachia.

Kari Gunter-Seymour is the poet laureate of Ohio and recipient of the 2021 Academy of American Poets Laureate Fellowship. Her previous collections are A Place So Deep Inside America It Can’t Be Seen (Sheila-Na-Gig Editions, 2020), which won the 2020 Ohio Poet of the Year Award, and the chapbook Serving (Crisis Chronicles, 2018). A ninth-generation Appalachian, she is the founder/executive director of the Women of Appalachia Project (WOAP) and editor of Women Speak, the WOAP anthology series, and of I Thought I Heard A Cardinal Sing: Ohio’s Appalachian Voices, a one-of-a-kind anthology funded by the Academy of American Poets and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. She is the founder, curator, and host of Spoken & Heard, a seasonal performance series featuring poets, writers, and musicians from across the country; an artist in residence at the Wexner Center for the Arts; and a 2021–22 Pillars of Prosperity Fellow.

You are a champion for the unheard voices of Appalachia, and this torch-bearing began with your powerful chapbook, Serving, and first collection, A Place So Deep Inside America It Can’t Be Seen. Can you talk about your new book, and how it continues the work of the previous two?

In the beginning, I had no formal training in writing besides college composition. I was attending workshops located North of me in Ohio. When I started going South for workshops, I suddenly realized this is why I always feel different and stand apart. I realized a good reason people don’t get my work is because I’m Appalachian.

I always knew I was different, and I thought that was because I was farm-oriented and I’m crazy about the land. People called me a tree-hugger and all that. I let people talk me out of my twang. I went for many years where “I spoke like this” (insert neutral non-accent here) because the twang was just not acceptable. And I finally decided I’m just not doing that anymore because this is who I am. This is how my granny talked, this is how the people in Tennessee talked, and I’m going to talk the way I talk. So my writing is really just about that. It’s about my people. I started doing the research and found out I’ve gone back 9 generations in Appalachia.

The other thing I write about is the military, because I’m a military mother. The chapbook was about surviving while my son was in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. So all of that is to say I literally write what I know. If I go outside of that, I do a whole lot of research, but I always come back to home soil because that grounds me and is who I am.

The South, and in particular Appalachia, bears long-held stereotypes that your poems are able to unflinchingly address, and then redress. Have you seen those perceptions change at all in your lifetime, for better or worse? How do you think poetry helps illuminate the other side of those stereotypes (yours in particular)?

I think it’s ironic because the pandemic was really an opportunity for poetry. I think that people were embracing poetry so deeply because of that need for comfort and for real, true information. Since the 2016 election, people have turned to poetry because they want the truth. Poets are truth-sayers. They can’t help themselves. We just can’t help but blurt out what we think and what we know. Because of that, I think poetry really has taken on some power. I know throughout history it has done so as well, but I think it’s in a Renaissance again.

Concerning Appalachia, I think there are a lot of us out there trying to make that happen. People come to mind. Of course, Silas House. Rebecca Gayle Howell, Nickole Brown. Carter Sickles. Oh, my gosh. Wendell Berry, Nikki Giovanni, Dorothy Allison — folks who have been for many, many, many years trying to spread the gospel of Appalachia. Now there’s a handful of others of us who have come up.

The aging process, and its connected themes of coming to terms with our relationships with our parents, our bodies, and death are a connecting thread in this collection. How has “maturity” changed your writing or process?

I’ve only been writing since 2009. For me, since I’ve really only been writing a handful of years in poet years, I don’t know that I’ve changed, but I think the word matured is appropriate, not just even in age, but in my voice. I’ve become a better poet. I’ve become a better journalist. I use the word “journalist” lightly. I think, too, I’ve built my courage to share my stories, because a lot of them are intimate stories. I feel compelled to share them to encourage others, or to tell others, “Hey, you’re not alone. Look, I’ve gone through this, too.” I’m taking on the tougher topics and trying very hard not to be angry. I don’t want to come off as angry. I want to come off as the real feeling I’m having, because lots of times we know the anger comes from fear.

Tackling tougher topics in a personal way can be very difficult to do as a writer. How do you go about it?

I think maybe that’s how I deal with my fear and angst. Writing poems is so therapeutic for me. I get done with them and put them away for a while. Later, I come back to finesse them.

This is what I tell my students. I have worked with incarcerated teens and adults and women in recovery housing. This is how I encourage them all to write. Journal it. Get it all out on the page so that you can look at it. You can observe it, not as the person writing, but as one person away from it. Read it as though you’re not the person who wrote it. That way you can organize it on the page. You can bring order to your chaos, so to speak.

Alone is a masterclass of creating a “sense of place” on the page, in this case, your beloved northern Appalachia. Part of the way you do this is your use of sound in your poems. Is this musicality something you work for or does it just flow that way?

Thank you. I’ve been hearing that a lot lately. We sometimes don’t recognize that about ourselves. But honestly, I think that musicality comes from my grandmothers because they had that music in their voices. That’s the twang. That’s the mountains. That’s the creeks. That’s the rivers. That’s the fields, the pastures. That’s the wind. That’s the gardens growing and during the harvest, and the breaking backs with women out there working with children tied onto their backs. That’s the musicality. If you just let it come, it comes. It’s not something that I own. It’s something that I’m given.

I know the Women of Appalachia Project is close to your heart. Can you tell us what you’d like us to know about the project?

Yes! We’re coming up on the 15th year of the project. I am the only employee. I don’t get paid. This is my service. I had so many opportunities as a young Appalachian single mother. I realized I had to get into college or my son and I were going to be living as low-income all of his life. Don’t get me wrong, not everybody gets the opportunities that I did. I was able to take a class at Ohio University, and the teacher was a single mother, like me. I did so well that she connected me with other people at the university to help me apply for scholarships, and got me enrolled, and just found every opportunity they could for me to help me enroll full time.

After graduation, I was doing graphic design, and I still loved to write, but I realized early on that writing might not get me a paycheck. I was doing some writing and fine art photography and submitting to different venues and getting back rejections. But they were really weird, saying, “You’re so ethnic. Where do you get these words? Why would you send us a picture of someone standing in their muck boots in a mud puddle, in a dead garden?” It got back to that whole thing about they just don’t understand this part of the country.

That’s when I decided, hey, I’m a graphic artist. I know communications and marketing. I can do my own art show, and I can do my own reading. I can have my own book. The first year I started out with five fine artists, and four women read their poetry. I got a lot of great feedback about that, and later partnered with the Multicultural Center at Ohio University. Our anthology, Women Speak, supports readings all over Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky. Now we’re going to be moving down into Tennessee and North Carolina, too. Hundreds of Appalachian-based women have participated over the years. It’s become a sisterhood of voices, standing up for Appalachia.

That is fantastic. It has been such a pleasure to talk to you and I thank you for your time. Readers can look forward to Gunter-Seymour’s collection coming out in September and learn more about the Women of Appalachia Project.

Alone in the House of My Heart

By Kari Gunter-Seymour

Swallow Press

Published September 27, 2022