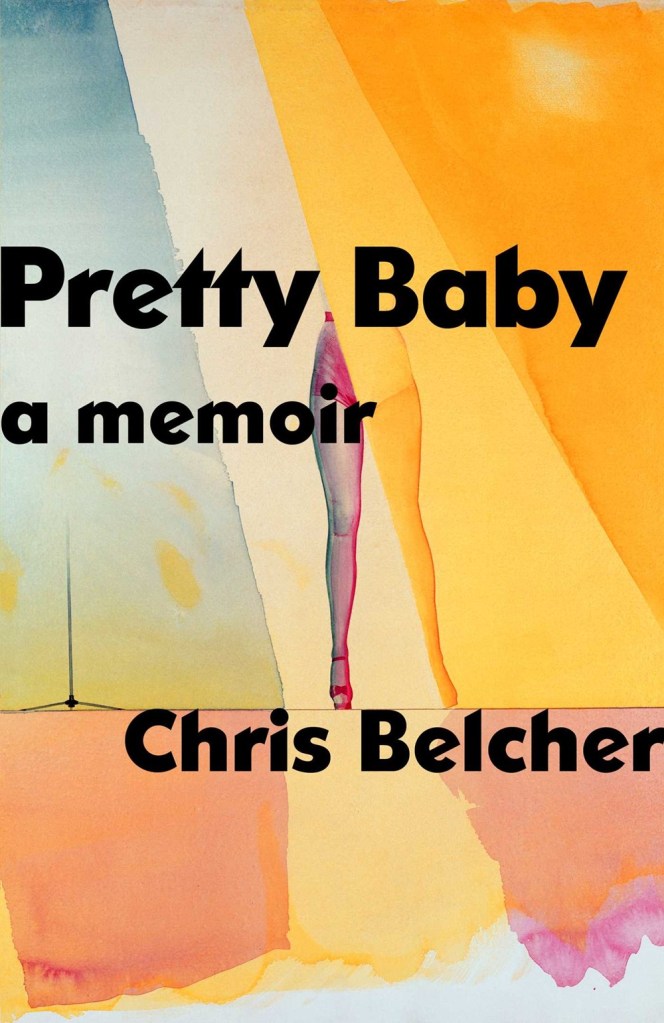

Chris Belcher’s memoir, Pretty Baby, begins the same way as many other new beginnings — without a clear destination. It is a collage of moments pieced together, seamlessly building the narrative of Belcher’s life and the journey of her coming out not once but twice.

In this memoir, Belcher offers moments spent with her father, friends in elementary school, her first serious girlfriend, and her emerging identity as a dominatrix. These images are woven together so that one memory shares space with the next until the entirety of Belcher’s journey becomes clear. There is little filter offered to readers in this memoir; this is a brutally honest collection of images focusing on a life spent redefining what it means to be feminine.

Belcher’s contemplation of identity, and by extension femininity, begins early on in the memoir. In chapter two, just after Belcher’s failed attempt at losing her virginity, she allows others space to join her in contemplation. “I laid beneath him and stared up at the glow-in-the-dark stars, peeling one-by-one off my bedroom ceiling, and imagined wanting something more, not yet knowing what it would feel like, or what it could be.” Though this is not the first event in Belcher’s life leading her to question her identity, it is one of the first clear indicators of the greater questions Belcher seeks to answer.

Though the memoir first introduces Belcher from a much later time in her life, Belcher’s memories chronologically begin with a blue ribbon at the county fair’s pretty baby contest. The importance of the infamous blue ribbon, of Belcher’s celebration as the prettiest baby, moves in and out of the text, though its image is never far outside the frame of Belcher’s life. It serves as a constant reminder of what femininity should be according to small-town Appalachia, where her life began.

Her connection to her hometown is never completely out of the picture. In chapter sixteen, during her first year of dissertation research, Belcher makes the trip to Washington DC, her father driving the six hours east to join her on her last day there. “Dad hugged my shoulder into the snug of his arm while we walked. He loved me like he had before he knew me, before I knew me, before I went and ruined what we had.” Belcher again defines herself by the standards of feminism she no longer lives by, a standard she can’t help but feel measured by when embracing people from her past. It is a reminder of what she has given up in order to embrace her true self.

Though this memoir explores identity through the pleasure of others, Belcher’s transformation into a domme doesn’t truly begin until chapter thirteen, where her other persona is born. To her clientele, she is Los Angeles’ Renowned Lesbian Dominatrix. She trades her short hair and more traditionally masculine style for long hair and lipstick because dommes are often seen as the id of the feminine identity, the type of woman that says and does what other women are afraid to do. In some ways, this image conflicts with the hard-edged punk rocker Belcher encourages others to see her as in her day-to-day life.

As a domme, Belcher is in charge of sessions and scenes for paying clientele with high expectations. Dommes share intimate and sometimes embarrassing experiences with their clients, knowing that a shift in power could happen at any moment with disastrous results. A successful scene, according to Belcher, is often measured in blood, purple bruises, and ejaculate — which she would have to clean from the room. Belcher admits the frail boundaries of her work as a domme: “If you hurt enough men, you might for a time, forget to fear them. They will remind you.” Clients turning a scene is constant fear — though they are called kittens, soft and fluffy they usually are not. Trained in self-defense, she and other dommes work with a constant fear, a constant set of rules they are never meant to break.

As a dominatrix, Belcher found herself working as the “id of American femininity,” meaning she has the capacity and authority to say no. But Belcher often found herself at odds, separating the two identities dwelling within her, and as an individual outside of her work “still hadn’t gotten the hang of saying no.” The art of saying no is something Belcher stresses all women should work on, that “it is the failure of femininity to do as it’s told” — a failure Belcher encourages women everywhere to aspire to.

The dominatrix in Belcher seeks to redefine the boundaries of femininity through the intimate and often painful unraveling of self. Belcher calls others to join her on the journey of self-discovery and exploration in a way that leaves readers feeling raw. When she exposes the unbridled id of the femme fatale that can be found in women everywhere, readers are prepared and willing to listen. Pretty Baby not only redefines what it means to be women, it is a call to action for the next generation.

NONFICTION

Pretty Baby

By Chris Belcher

Avid Reader Press

Published July 12, 2022

Reblogged this on Jessica Blandford and commented:

Another great read!

LikeLike