Mesha Maren is an Associate Professor of the Practice of English at Duke University, and her new novel Shae is a brilliant addition to her impressive list of publications. In Shae, Maren depicts her own hometown in West Virginia as a site of young queer love and heartbreak. The novel is a triumph of careful attention to craft, place, and empathy, and it is populated by characters you’ll want to know more about.

Shae begins with the narrator recalling the first time she saw Cam walking into the Greenbrier East gym in her Tool T-shirt and Jnco-style jeans. From there, the narrative unwinds in past tense as Cam and Shae find themselves evolving in ways that are both separate and also deeply entangled with one another. After a traumatic C-section, Shae slips into opioid addiction, and meanwhile Cam begins a completely different type of transformation, as she leaves Greenbrier County to attend college in Charleston, WV.

I recently had the pleasure of talking with Mesha Maren about her writing process for Shae and the real world places and experiences that shaped the narrative.

When we talked about Perpetual West, you said “I get sort of obsessed with place and landscape and character’s relationship to place.” I am also from southern West Virginia, so I noticed that the locations in Shae are real world places. Why was it important to ground this story in real geography and place names?

I can’t imagine it anywhere else. Every road that Shae drives down, every town that she goes to, every gas station that she stops at, I was picturing the real thing as I wrote it. For some people, like you, you know the references, and for other people, maybe it won’t make as much of a difference if they don’t know what Keeney’s Knob is and I could have named the mountain anything. But it very much mattered for me when I was writing it.

This is the first book I’ve written entirely while living in West Virginia. Most of the narrative drafting happened during the pandemic, and I was completely in West Virginia. So I had notebooks full of notes I had been taking since 2017, and then spring 2020, I basically completed the first full narrative draft of it in like four months. I was not only not leaving West Virginia, but I don’t think I left Greenbrier County the whole time.

It was awesome to read a book that’s set in places that are familiar to me. Are there other novels, films, or shows set in familiar places for you?

Back in the winter of 2013 Two Dollar Radio sent me a book to review. I had been reviewing books for them for a little while but I didn’t know anything about this new book they sent me. It was Scott McClanahan’s Crapalachia. He’s from western Greenbrier County, and I immediately recognized lots of places. When I got to the acknowledgements, he was thanking people who I knew personally. I ended up reviewing it for HTMLGIANT. Before reading Crapalachia I had read Breece D’J Pancake stories. Those are mostly set in real West Virginia places, and they felt familiar, but sort of distant familiar both in time and space. After reading Crapalachia, I quickly read all of Scott’s work, and it’s all basically set in Beckley or in Greenbrier County or Rainelle. That was an incredible experience for me to read that.

In his blurb, Carter Sickels says “The sentences shimmer with precision, elegance, and grit,” and I wholeheartedly agree with him. Are you a writer who spends a lot of time on individual sentences and word choices? What does that part of your process look like?

Yeah, I do. I think sometimes that I care more about the sentences than I do anything else in writing or I care first about the sentences and then other things come into place. The rhythm of the words, the way that the sentences interact with each other, but even within a sentence the way that the individual words kind of bump up against each other is all super important to me.

I write longhand on a legal pad, and I read it out loud to myself. I pay attention to the rhythm of the words, but also the early drafts look crazy because I will have a sentence and then I will have spoking out from it all these different possibilities of words. Maybe it’s this word, maybe it’s that, and I’ll have like three or four options often. When I finish a draft I move to the computer, and that’s when I start to narrow it. If I had like three options for myself to describe a tree branch, then I’m like “which one is it.” Then it often changes again in the future. In the later drafts, I won’t move on until I feel like there’s something about the architecture of this sentence that’s as near perfect as I can get it.

It becomes clear early on that Shae is narrating with the benefit of hindsight. Was that structure something you were interested in from the beginning, or did you have to get the narrative in place before you could depict her thinking about events in that way?

This is the first time I’ve written a full manuscript in first person. I had written short stories in first person but never a novel. It was very clear to me from the very beginning that it would need to be first person. I’m a very visual writer, so all of my books have begun as images. Shae was the same way. In my mind, there was a young woman on a blue couch, by herself, spending a lot of time laying on the couch, but this one was very much like I was seeing through her eyes. I was a little worried about my ability to write a full novel in first person, but it was very clear that’s how it needed to be. So I either had to write it in first person or not write it at all.

But I didn’t plot out the narrative. I actually wrote it very impulsively, and the chapters were in a very different order. I sort of treated them like short stories. I wanted each of them to have the feeling that it could stand on its own, and they were not in chronological order, that’s just not the order that they came to me in, so I put them down in the order that they came to me. I knew she survived; I knew she outlived these experiences and was reflecting on them, but I didn’t know exactly what happened.

I found myself wanting to know more about Cam, and I can imagine an alternating narrative or even a whole other book of Cam’s perspective. How did you decide which of these characters to focus on?

It didn’t feel like a choice. Obviously, I know on one level that I’m always making choices, but some of the elements of the narratives I write feel like they are already true when the story comes to me.

When I looked back recently at those notebooks [from 2017], it was Shae. It was Shae in the beginning. It was Shae on that couch at home alone. Then, after a while, quite literally, other characters began to arrive. A car pulled up in the driveway and there was Shae’s mom and there was Cam. It became clear to me that Cam and Shae’s mom, Donna, were the other two really important women in Shae’s life, the important people in Shae’s life, but it was always Shae’s story.

Shae has been described as a “queer coming-of-age novel” and “essential for the new queer canon,” and it certainly is. At the same time, these characters are much more than their “queerness.” How would you describe the different ways that Shae and Cam come to understand themselves (not only in terms of gender / sexuality but also things like “capability” which is how Shae sometimes describes Cam)?

I had a conversation recently with my sister, she’s a mother of two teenagers, and one of the things she said was she felt like Cam and Shae’s sexuality and the ways that they talked about or didn’t talk about it were really true to what she has experienced from her teenagers and how they interact with their sexuality as not being something separate from other parts of who they are and also not being the defining thing about them.

For my generation, your coming out story was huge. Right, like when did you come out and how did it go?, and I’m sure that’s still a part of many people’s narratives, but I do have the feeling that things have shifted. The fluidity of both Cam and Shae’s sexuality and the conversations or sometimes lack of conversations around it felt very real to my sister in terms of the conversations she has had with her teenagers, and I was glad that came across as being real.

A big thing with Cam and Shae too, that I think Shae begins to realize, is that Cam came up against adversity in a really hard way. She was raised by a mother who was dealing with addiction, and Shae does really start to be able to see that even though she comes from a very working class family, she never wanted for anything. She always had enough food and had everything that she needed in a physical sense, but also she never doubted that she was loved, and that has not been true for Cam.

When we last spoke, you were the National Endowment of the Arts Writing Fellow at the Federal Prison Camp in Alderson, West Virginia. How did your work there inform this novel (if it did)?

Sadly the pandemic put an end to that way of teaching incarcerated folks in West Virginia for me, but I’m going to be teaching a class soon in the Butner Federal Correction Center down here in North Carolina.

The whole last chapter of Shae was heavily influenced by the teaching I did at medium and minimum security prisons in Beaver, West Virginia. A lot of the details about the daily schedule in the end and the work she does in the cafeteria, and then also there’s a particular part where she’s taking a writing class as part of a drug rehabilitation program, and she passes a magazine article to her teacher and gets kicked out. I was the teacher in that story in real life.

One of my students left a Sun magazine article for me in my mailbox that was about a woman teaching English in a juvenile facility. I knew and I always said to the students, I am only able to give to you the short stories and essays that have been approved, and the rule was that inmates were not supposed give anything, not a pen or a pencil, nothing, to me, but one of my students photocopied the article, and put it in my mailbox. I came there once a week, and the education director usually previewed whatever I was going to teach, and this magazine article was there. He read it then realized it had come from an inmate, and he was really angry because he felt like the depiction in the Sun magazine article of the Bureau of Prisons was negative. He got [the inmate] kicked out of my class, kicked out of the drug rehabilitation program. In real life the super heartbreaking thing was that he was in his seventies, in for a marijuana charge, and he was supposed to get 18 months off his sentence for completing the drug rehabilitation program, part of which was to write a self-reflective narrative of his experience of addiction which is why he was in my class. As a result of getting kicked out, that 18 months was put back on his sentence, and he had a heart attack and died in prison before he got released. It was fucked up, and I was so angry about it, and there was nothing I could do. I had contacted someone higher up to try to protest his being kicked out of the program, and was basically told that I had no power to change that. I put a version of that in the book because it felt like the only thing I could do was write about it because I was completely powerless in the moment.

The novel is deeply empathetic to Shae’s experience of addiction. In researching this novel, I suspect you found a lot of resources and organizations working to mitigate the ongoing opioid crisis. Are there resources or organizations that you think more people should know about?

I have a friend who does incredible harm reduction work. Her name is Sarah Danforth, and she works with Prevention Point Pittsburgh. They do a lot of incredible work in Allegheny County up there in Pennsylvania. In 2017 there were 700 overdose deaths in Allegheny County, but there were 600 people whose lives were saved because they used naloxone and reversed the overdose. So if it weren’t for the harm reduction work there would have been twice as many deaths in Allegheny County that year. I thought that was particularly interesting because that is the time period that Shae is set in. There’s lots and lots of organizations, but I would particularly like to highlight Prevention Point Pittsburgh.

There are also frequent music references in the novel. Can you tell me a little more about what you chose to reference and what those artists mean to you or to the characters?

I made a playlist on Spotify that has every song that is mentioned in the book.

I think part of why there’s so much music mentioned in this particular book is that I was thinking back to when I was the age that the characters are, and music was important in a certain way, in a way that was so defining. I felt like in high school, I figured out what kind of person I was and who I was going to be friends with through bands. You know, you would see somebody wearing a band t-shirt, or you would hear somebody with a song on in their car, and it was a point of immediate connection. It’s probably true anywhere, but I grew up in a rural space, so it seems particularly true there. When you flipped on the radio, the main thing available was country music, which I love a lot of country music, especially older stuff, but as a teenager, I wanted something else. Subculture was really important, and most of the time for me, subculture was formed through music.

Do you have a favorite metal or black metal band?

There’s a lot of them mentioned in the book. The last live show I saw before Covid was two of my favorite bands, and it was Neurosis and Wolves in the Throne Room, and it was an incredible incredible show. I’ve listened to them both, particularly Neurosis, for a long time, getting to see them live was amazing.

FICTION

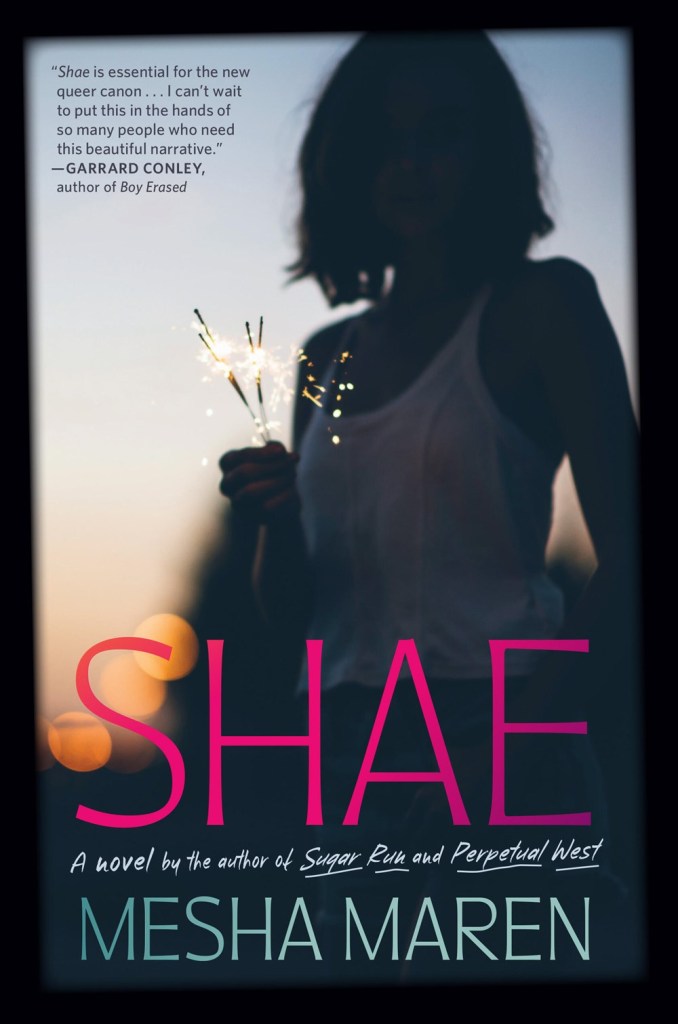

Shae: A Novel

By Mesha Maren

Algonquin Books

Published 21 May 2024