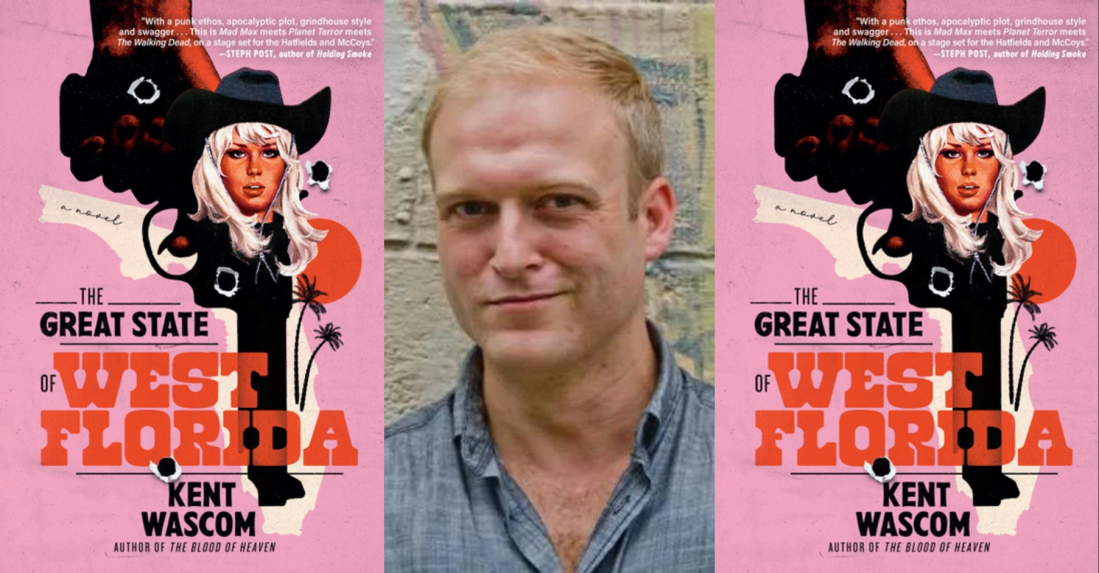

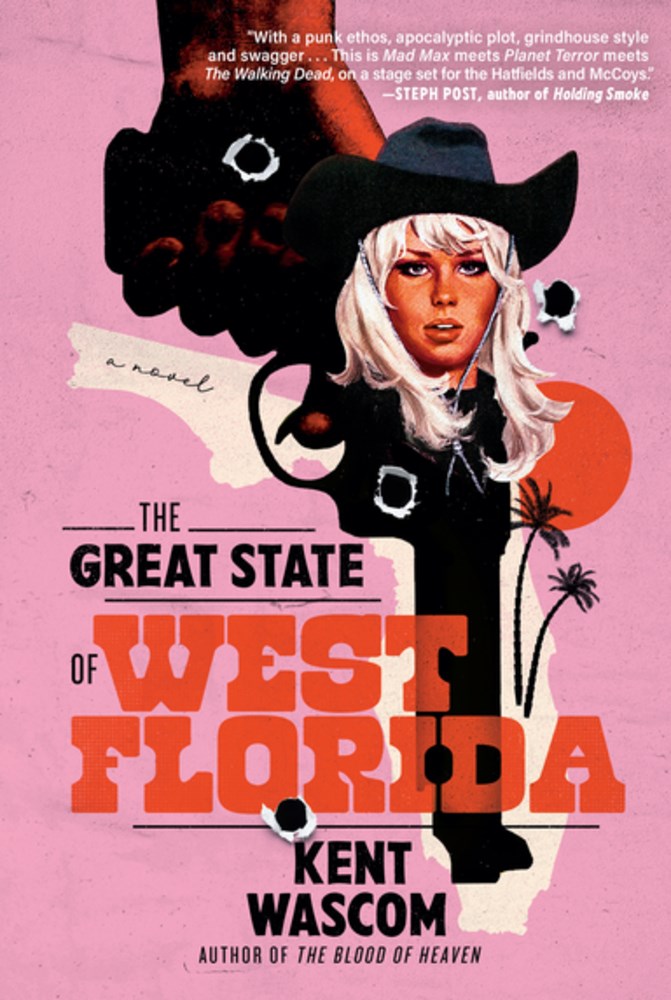

Kent Wascom’s new novel The Great State of West Florida is both familiar territory and a departure. Like Wascom’s other three novels, the new one revolves around the fictional Woolsack family and takes place up and down the Gulf Coast. And like his debut, The Blood of Heaven, Wascom’s latest is something of a “punk-rock Southern gothic,” as he calls the former, chock full of rough characters, colorful language and keen insight into the violent machinations that shape much of society. What sets The Great State of West Florida apart from Wascom’s other books is that it takes place in a speculative near future, rather than the past, and that future does not look too bright.

The story is told by Rally, a precocious and sensitive thirteen-year-old boy from Louisiana, who pines for belonging and familial connection. When Rally’s absent father, Rodney, a professional gunfighter, comes to reclaim his son, the adventure truly begins.

The novel examines the ever-widening social rifts in the South and imagines just how vast those fissures can become. Spoiler: violence, violence and more violence. But against that backdrop we find community and love. We come to discover that old family bonds are impossible to break. Rally is a wonderful character, as is Destiny, his enigmatic cousin, a freedom fighter with an artificial golden arm. This novel is a literary fictional take on Manga, a new Southern Revisionist Western and something else unclassifiable altogether.

Wascom is the author of The New Inheritors, Secessia and The Blood of Heaven. He was born in New Orleans and raised in Pensacola, Florida. The Blood of Heaven was named a best book of the year by the Washington Post and NPR. It was a semifinalist for the VCU Cabell First Novelist Award and longlisted for the Flaherty-Dunnan Award for First Fiction. He lives in Norfolk, Virginia, where he directs the Creative Writing Program at Old Dominion University.

The interview was conducted over email and later Zoom in April and May 2024.

If you could have any director past or present adapt The Great State of West Florida to the screen, who would it be and why?

The book’s built on a whole lot of influences, but anime (particularly the movies and OVAs that were available to Americans in the early 90s, the stuff I saw as a little kid) are the heart of the book. I saw the characters as drawn by different artists, like Leiji Matsumoto or Masamune Shirow or Yoshikazu Yasuhiko, and there are nods to theirs and others’ work throughout the book (I also dedicate the book to about a dozen Japanese artists). But in terms of directors who are no longer with us, I would have to say the animation director Satoshi Kon (Paprika, Millennium Actress), whose unrivaled mastery of sequencing, montage, and depicting layers of reality, really makes him feel like someone who could do great things with West Florida’s world of competing psychopathologies, to borrow a phrase from J.G. Ballard.

I asked that first question because I happen to know that you enjoy overlooked low-budget action movies, and a perceptive reader will notice B-movie and pulp fiction tropes and references throughout The Great State of West Florida. Tell me about your love of these movies and paperbacks and how they informed this novel. I’d also love to hear your thoughts on the divide between so-called “high” and “low” art.

As a little kid, around the time I was watching things like Galaxy Express 999, Dominion Tank Police or The Venus Wars for the first time, I was also beginning to collect paperback sci-fi, horror and crime books. I think growing up in the shadow of Gen-X, the great appreciators of bygone cultural ephemera, really helped instill an interest in what some would call trash culture or pulp. I was also reading traditional literary fiction, trying out The Great Gatsby or The Pearl and stuff like that. Other than a brief period in undergrad and grad school where I got too cool for (pulp) school, that’s how it’s always been. I don’t think of it as alternating between “high” or “low” but between different generic conventions and modes of storytelling.

One of the current directors I love is Nicholas Winding Refn — the way he treats ostensibly pulpy or exploitative elements with reverence or subversion, anything but contempt or a knowing wink, and processes them through his absolute commitment to a distinct visual style. I say ‘process’ and not ‘elevate’ because I don’t think genre or the elements that align with various genres need to be elevated. Panos Cosmatos does this, too, as do many other directors. My favorite artists, like Angela Carter, queen of my shelves, are all, primarily, stylists who acknowledge the material they’re interpreting. Jerry Lee Lewis always called himself a “stylist,” not a musician, and I think of myself that way, too. I take stories, historical incidents or generic elements, and interpret them stylistically. It may be somebody else’s song, but you don’t have to listen long to know it’s me playing it.

West Florida is your Yoknapatawpha County. But unlike Faulkner’s fictional county, West Florida was (briefly) a real entity, extending from the Florida Panhandle to Southeastern Louisiana along the Gulf Coast. The history of that location provides a backdrop to your fictional Woolsack family as they move from generation to generation, from the late eighteenth century onward. How do you walk the line between actual history and your own mythmaking?

I’m a big fan of mythmaking when I’m the one making the myth. (Part of the deal with The Great State of West Florida is re-mythologizing the Western, for example). But when it comes to the history of my larger region, the Gulf Coast in particular and the American South as a concept, I want to be as true to the unreal beauty and horror of that place and its history as possible. I never wanted to write stories about ultimately good Southern white people doing their best in trying circumstances. The conflicted confederate soldier, et cetera. I wrote one book about a good person (The New Inheritors) when I was flush with love and beauty in my daughter’s babyhood, but to balance that choice I used a Jim Harrison or even Victor Hugo-style voice where I could stop, as the authorial persona, and harangue the reader on various topics.

If I could really flatter myself, I’d say that since West Florida doesn’t exist in a formal sense, then I get to shape its mythology in my own way.

Speaking of Faulkner and the South, what are your thoughts on Southern literature as a category and how do you see yourself fitting within that category?

I feel very fortunate to be a Southern writer, as long as the definition of Southern is as generous and nimble as possible. It’s a literary tradition readers around the world respond to, and that’s a gift, much less the fact that it embraces the grotesque, the baroque, or at least that’s the part of the tradition I feel most at home in. Like any genre, though, it’s a whole lot more than its most obvious and well-worn signifiers. It’s no accident this book starts with a quote from Harry Crews (Karate is a Thing of the Spirit), though. Of all Southern writers, this book is deepest in his debt.

Can you talk about your writing process? How does a book, say, this latest book, go from an idea into a finished novel?

This book had the longest, hardest road from inception to publication of any of my books. Walking the tightrope of a novel without the net of history was something I hadn’t done since, I don’t know, 2005, when I was in undergrad. So without that sense of security or structure, this novel took shape around the motifs and elements of popular culture, particularly mass market paperbacks, anime and the Western. But that wasn’t until really close to the end of the drafting processes. Before the serious revision started. I revise daily when I’m working on a chapter, which makes things very slow sometimes, but I love fiddling with words. Anyway, originally, for several years and many drafts, this was a big old deadly serious novel of braided stories about a conflict between right wing militias in the Florida panhandle, something closer to what Alex Garland’s Civil War seems to be, funnily enough.

As the Trump years went on, I kept having to throw material out because the world kept on lining up with it too closely, so finally I stopped chasing what would or could happen and wrote what did happen. Meaning, I abandoned the predictive stuff and tried to tell a story like it was written on an obelisk in the future, like what Denis Johnson did with Fiskadoro, or Joanna Russ with The Female Man. But even that choice didn’t get the book over the hump. It was still a big, baggy pseudo-epic following many characters in nested novellas. It was only thanks to editors Emily Burns and Peter Blackstock that I finally took the plunge and whittled the book down to one point of view, Rally’s, and let the story go through him. That changed everything. I was writing entirely in first person for the first time since The Blood of Heaven, which felt really fun, and the book as it exists now really took shape.

Unlike previous novels, which were set in the past, The Great State of West Florida takes place in the near future. How do you see this latest novel fitting into the overall project?

So one of my fundamental storytelling influences is this show called Robotech (1984), which I saw as a little bitty kid. Romance, onscreen death, an interracial relationship, coupled with pop music, interstellar warfare and giant robots — it’s amazing. Tons of references to this show in GSWF, by the way, particularly in the form of Claudia Laval and Riley Rae. Anyway, Robotech (or the first season at least) is the localization of an Anime called Super Dimension Fortress Macross (1982). At the height of that show’s success in Japan, they made a movie called Macross: Do You Remember Love? (1986), but the movie isn’t just a retelling of the series, it’s a movie made within the world of the series about the events of the series. It’s a movie the characters from the series, or people in their world, could go and watch, which acknowledges the differences and liberties taken with the source material and puts the viewer in a really interesting interpretive position.

This is a long and ropey way to say that’s what I wanted to do with GSWF. This book is the mass market paperback that characters in the timeline of my historical novels could read. That’s a big reason why we put it out in paperback, to distinguish it from the books in the series proper and of course to embrace the form that really inspired the book.

Violence appears all through your books, but in this one it’s often approached with levity and even humor. How did you think about tone as you wrote this book?

As Claude Rains’s character says of O’Toole’s Lawrence, I have a funny sense of fun. Artistically, I really appreciate stylized, balletic depictions of violence. (I appreciate wrenching realism, too, but in a different way, of course.) And I really embraced both the extremity and the hyper-stylization of violence in this book. But when the events were told in a momentous, removed voice, they sounded miserable. Flat. Grim. Rally’s point of view changed everything. The way he sees the world, his misunderstandings or mistakes, give the story comedic beats and points of release amid the tension and nastiness.

As I read this novel, I had the feeling that it was your most personal book. Do you see it that way? It comes across as both a love letter and a strong critique of the place where you grew up.

It definitely is. We moved from the North Shore of Lake Pontchartrain to Pensacola when I was little, because my dad, like Pawpaw in the novel, went to federal prison. I grew up in Pensacola, visiting Louisiana almost every weekend, so as a dumb teenager I developed this identity of hating Florida, hating Pensacola, hating the beach, and styling myself as being from Louisiana. Come to find, when I move back to Louisiana for college, everybody there tells me I’m from Florida. Around this time, I learned about West Florida — that everywhere I’ve lived was once connected, that it just as easily could’ve been a state. So then I had the best kind of place to write about, a dream space, one I could define and develop over time. This novel, and all of my books so far, are in some way defining that sense of self and place. I can’t be an authentic Louisianan, or an authentic Floridian, or this or that kind of Southerner, but I can damn sure be a West Floridian.

What’s next for you, if you don’t mind sharing. Do you plan to carry on this series to six books, as I’ve read before, or venture out into new territory?

I want to pick up the novel sequence again at some point, but where in history I’ll go is still up in the air. Right now I’m doing research for a crime novel based on some family history. My father’s cousin was a safe-cracker who robbed banks with Frank Lee Morris, of Escape from Alcatraz fame. In the summer of 1955, when Elvis was crisscrossing Louisiana, the two of them escaped from Angola (with a little help from my great grandmother), tagged up with a friend in Kansas City, and went on what the papers called a “three-man crimewave,” culminating in the crime that would send Frank to Alcatraz. But these guys were smart, they were burglars, not smash and grab robbers. Frank Morris doesn’t even have a violent crime on his long, long rap sheet. And from what I understand my dad’s cousin wasn’t violent either. So I’m excited to write a story where the only people waving guns around are the cops.

Other than that, I still haven’t stopped writing and thinking about the world of West Florida. Like you said, it’s so personal, and so damn fun to write about that place and these characters that I wouldn’t be surprised if The Great State of West Florida didn’t kick off a whole new set for me. The weird thing is, when I reapproached the book and really embraced Rally’s voice, I said to myself I was going to treat it like it could be my last book, so I was going to cram as much of what I love or am obsessed or haunted by into it. And that feels really good.

FICTION

The Great State of West Florida

By Kent Wascom

Black Cat

Published May 21, 2024